Blue Prince (PC): The Art of Intuition

It's a classic setup: You can inherit a stately home but under a strict condition. In Blue Prince, that condition is make it to room 46, that's room 46 in a mansion where – as you can see from the blueprints – there is only space for 45 rooms. It's the first hint at the trickery up Blue Prince's sleeve, a game of lateral thinking that is textually about journeys rather than destinations. There's a lot more narrative but everything is in the same style: complexity hidden under simplicity. At every level the game is this, every mechanic and wider approach cohesively aligning to a singular experience. It is an experience of puzzles within puzzles within puzzles, one overarching mystery that – in its pursuit – just opens up a deluge of further things to uncover.

The game is built around intuition, with every mechanic and design ideology focused on making you pause and concentrate. In it simplest terms, Blue Prince is a take on the run-based genre (a rogue-lite, if you will). It's also arguably a deck builder, but let's not get ahead of things. The core loop is that every day you can enter the house and build its layout. The house is different every time: a 5x9 grid of potential rooms. In a room, and outside of the house (and, of course, there are things to discover out there), it's a first person exploration game. However, as soon as you go through a door into where another room should be, you are then tasked with drafting (from a list of three possible rooms) what that room will be. There's a degree of randomness but you are pulling from a defined list of rooms (and can only draft each room once per run). You can bring up the list of rooms to check it, but if there's a room you haven't been in yet, it won't show on the list yet. There are other things at play, though. Certain rooms can only appear in certain parts of the house; certain rooms have to be unlocked before you can draft them; certain rooms can only be drafted from certain other rooms (or are impacted by something you can only do in another room) and you can even find upgrades or items that skew things in your favour. Each room is different, may of them doing a defined thing or containing certain items: 'The Den' will always have a gem in it and gems can be used to unlock more complicated rooms; another room might be a shop; another a garage; another a bank vault. Some rooms have obvious uses that are spelled out and many of them have wider purposes you have to intuit. Another underlying mechanic is that, at first, you only have 50 'steps' per day, and every time you enter a room (unless it has a mechanic that shifts this) you lose one of these. Once these run out, your run is over and you start again the next day. Picking a room is a big decision, then, making you pause to intuit. Being in a room is an important investment, and you will soon find out that all kinds of things are hidden in plain sight, always requiring intuition.

This is the pace of the game, all pushed towards making you take time and take everything in. It is a lot of repetition but that repetition is needed because you need to work out how things fall into place. The game is stuffed with smaller and larger puzzles, and clues are in defined locations that can often shape how you see a certain room. For example, you may start to note that certain rooms always have a certain chess piece in them; much later, after a few important discoveries, you will find a puzzle that necessitates you know where these are and use that information. To play the game is to learn its wider design language, taking the time to intuit how it fits together and what is important. Because it is all built around thinking laterally and creatively, discovery is key. This is why the random element is integral. Yes, you will feel locked out of certain things – especially as rooms have a defined layout of doors, and they might be literally locked (and you may have run out of keys). You will draft your way into a dead end by just not having rooms available that can open up the path you need. But it's a game where failure is integral and the narrative keeps pushing you towards the point that it's not about the destination. Really, the Room 46 goal, though incredibly satisfying, is one small thing and is only really contextualised if you know a lot else. As you do successive runs, you will open up a list of things in your mind (or on your notepad) of questions you want to answer or tasks you need to do. The randomness makes you discover and work with what you have, forcing you to spend time in the same places and – if you're on the game's wavelength – start to cross reference what you know. There are permanent upgrades you can find and some of these really change how you play the game. Also, at a few points, the scope of the game changes and you realise there is so much more. You may feel stunted by the RNG of it all but this failure first design is a way of pushing you to look further than optimisation, and is the primary clue that success is differently designed. There is always, for tens of hours at least, many things you could be doing and it is better to think of runs as a way of working with the tools it gives you to learn more, rather than brute forcing your way down a fixed path.

There's a lot of narrative underpinning everything and, truly, the whole thing is narrative in the way only video games can be. The way things are always has an in world explanation and, even when you find one of many red herrings, you can work out – if you've intuited enough about the world – why it is a red herring and from that you can learn something else. It's the story of a family going back generations and of the world they exist in. It's all about learning, the game mechanics force you to learn and the story is all about doing the same. At every point, the experience is pushing you to a specific artistic vision. As you find out more about the world, it's deeply rewarding. The narrative plays with the idea that history is a process of intuition and of working out a theory from disparate evidence. The past not lived by us exists subjectively and, just as you figure the game out as you go, the game teaches you that learning about the world is the same thing. There's really compelling lore but it's also inherently thematic – and bends back into mechanics. You will learn very quickly that 'red rooms' are always negative, then you will start to learn why the people in this house, in this particular realm in this particular regions, would see red as negative. Through this you start to learn that everything is a clue but it's not just a clue in a mechanically, puzzley kind of way. You will make extant progress but the most satisfying part is just learning and uncovering – which is again mechanically encouraged. This has, unsurprisingly, made discourse about the game difficult. The more you play, the more you realise that everything is the way it is for a very precise reason and that what you earlier perceived as friction was part of a process training you a certain way and pushing you a certain way. The game makes you an apologist for it, in a wonderful way, as those (like myself) that find themselves completely drawn into the experience will start to counter every critique with things along the line of 'but that has to be this way because blah' and 'actually...'. This will be frustrating for some but it is just a game that demands you meet it on its level and rewards you exponentially for doing so. It's a seeing the Matrix process. Forty hours into the game looks, to the outsider, just like how things were a couple of hours in (with a few key differences). However, the forty hour deep player will look at the same room and see so much more, understand how so may more pieces fit together, while the early game player just sees stuff. It is inherent reward. You play to understand and there is this amazing philosophy at the centre of the game about the interrogated life.

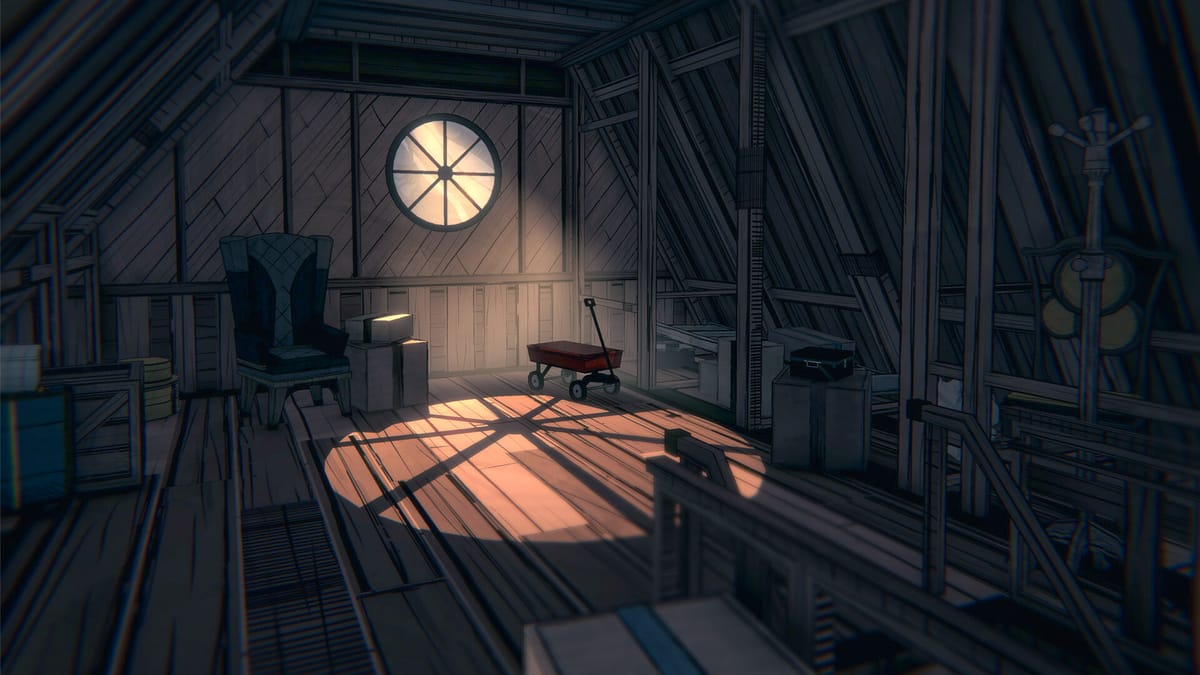

The aesthetics are aligned, also. The look is simple but evocative. A cosy style that is the perfect façade for complex – and at points quite dark – mystery. It ties back to how the game is very simple until you realise it's very complex. Even the drafting loops starts to get more complex, though it doesn't really change. You will learn strategies and can even find in game books that will teach you strategies, or just suggest them. You will become better at the central loop because you will start to understand the things that stay the same: it's about variables. Really, it has the skill arc of an action game which is why being focused on finishing things early will frustrate. You get better through learning about all the things that are set for you, and how the real game is about fitting what changes onto what is fixed. This may not sound satisfying to you, and that's fine. The game is at least cohesively built around this. The visual approach is simple enough to make key information obvious – so you can spot patterns – but also it obfuscates things. You can interact with quite a lot of things but you won't know you can interact with things until you learn elsewhere or stumble upon it. Some background details might actually be items you can use and, again, it's all about learning the language of the game itself. It is all built around facilitating attentive play, the mechanics gesturing you towards a play style where you are constantly on the lookout for things. You may find an item called the metal detector that shows you when there are hidden coins or gems in a room, or other key items (including keys). This is useful when you have it but it also illustrates that that's another variable at play: that you should be looking for hidden items that can appear. You may then find out that a certain room always has a computer that tells you what items are in the house. The game is full of interlinking elements and, even on 'unsuccessful' runs, you can really exercise mastery – and there's always something to uncover. Even the music is working with you: most of the time it's this serene, backgrounded melody – ambient. Yet, at key moments of realisation (there are certain points where you clearly uncover something), the music swells up to match. A bass clarinet is used really evocatively; incredibly moody music that fits the ruminative mood when it needs to, and then soars up to match the adventure. Again, it's wonderfully cohesive design.

All the writing is also phenomenal. You will read short stories, diaries, loads of notes. They have been written by people in the game's world and there is a real control of different voices. Your understanding of these different perspectives will help you with story and with puzzles, a phenomenal achievement where everything is designed in a way that facilitates narrative and that facilitates the puzzle focused gameplay. It's tempting to view the game as blend: a traditional style adventure game meets a rogue-lite deckbuilder (and some will argue that one may be at odds with the other). This duality helps to give an idea of what the game is but, most truly, this game is singular. The adventure game elements don't exist without the rogue-lite elements and the rogue-lite elements rely on the adventure game elements. All this becomes clearer the more you play. It is truly a game of jaw dropping discoveries, a game that continues to unveil itself and expand its possibilities. If you connect with it, it's an all consuming thing – and so satisfyingly so. A rich narrative experience that imparts everything in a way only video games can: a proper narrative video game. It's a game with a philosophy, also, driven from every aspect. It's the subtext of the plot; it's the subtext of the mechanics: question things and don't let things stay the same for the sake of it. There's a note you will find at a relatively early point that makes a clear statement against tradition, and even the room drafting element (and the randomness) is a part of this. The world is a changing, unpredictable thing that does what it does regardless of us. Yet, we can still be engines of change and, we can equip ourselves with knowledge to become more effective agents of change. That's a thesis statement it works towards: question authority; think laterally; don't just accept things the way they are. The design of the game also pushes the player beyond it, a game that encourages conversation and collaboration, a sentiment rooted in its themes. We exist in set systems but not everything has to be the way it has to be, and we can do more than we think. Entering Room 46 doesn't matter, per se, the game continues and much more lies ahead. Getting there really matters, because process is key, and getting beyond it matter even more. It's trite to say that it's the journey, not the destination but this game takes that idea and gleans further philosophy from it. A staggering achievement of intentional design and one of the very rare games that reminds you of how special this medium is.

Comments ()