February 2025 Roundup

I should have finished this sooner. Let's not talk about it. Will my March article come out in a reasonable time? Stay tuned to find out.

Though it would have been nice and neat to start a monthly roundup post last month, there's no time like the present to create a new excuse to talk about some of the best films I discovered last month. It also seems like the ideal way to share any pertinent updates or generally yap about unrelated nonsense. February feels like a particularly light month at the cinemas for anyone whose awards season ended two months ago, a toss-up between awards contender rereleases, the last awards films to finally stumble out onto the big screen, and a handful of films that studios didn't want to give better distribution to. Which does occasionally bring you the likes of I'm Still Here, one of last year's best films and a potent vision of life under fascism – but also brings the likes of Love Hurts, which features the least amount of romantic chemistry imaginable for a film released on Valentine's Day.

What I'm never light on is the myriad of film's I'm constantly discovering, and it seems smarter to break it down each month rather than feel like I've missed mentioning countless films at the end of the year because I can't write a 100+ film long annual wrap-up article.

Finally, I'm thrilled to say my friend, podcast co-host, and fellow critic Stephen Gillespie will be joining Step Printed as a regular contributor. You can read his first review of Jia Zhangke's Caught by the Tides here, and look for more soon.

Discoveries

Across 110th Street (1972)

dir. Barry Shear

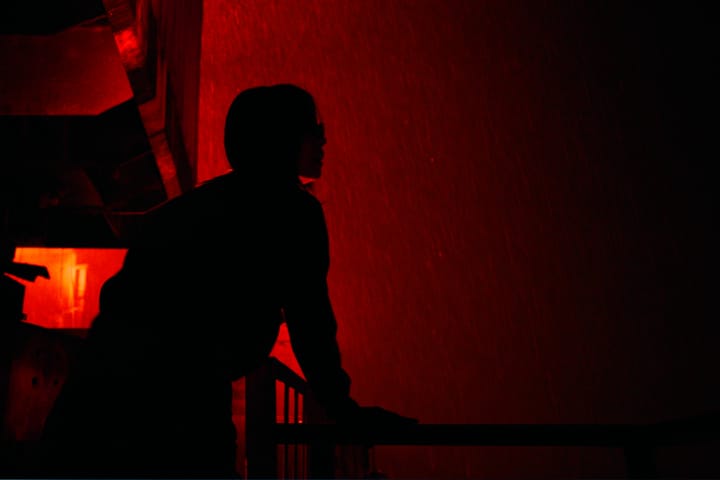

An American Years of Lead poliziotteschi. Gritty as hell, dust in the lungs and gravel in the cuts. Bookended by two violently bloody shootouts where Harlem boils over and explodes, opposing criminal enterprises reaching critical mass while a bloodthirsty archaic detective and his partner's no-nonsense progressive sensibilities light the spark to ignite it all. Caught in the middle is everyone else, widowed mothers and desperate burnouts who long for peace and stability, crushed beneath an unforgiving wheel of poverty, injustice, and violence. All of it hurtling into oblivion, shattered in the film's earliest moments where trust evaporates into thin air and bullets become the only viable currency in a world of death.

The Exigency (2019)

dir. Cody Vibbart

Blame it on my past life as an aspiring 3D artist, but something about The Exigency feels deeply resonant despite its outward appearance being that of an early aughts PS2 cutscene. A passion project of director Cody Vibbart, the entire film was animated in dated software over the course of 13 years. It's rough around the edges, but that's where the best films lie; on the fringe, or far beyond the boundaries of the traditional filmmaking process. It's easy to draw a line to the ferociously independent oddities that have come out of Nabwana IGG's Wakaliwood (Who Killed Captain Alex?, Crazy World) or the microbudget suburb cinema of Motern Media, but to put it next to anything would be painting it with too broad a brush, because there's really nothing else quite like The Exigency. It's the kind of film that beguiles under the auspices of some kind of "so bad it's good" umbrella (though I generally find the term a disingenuous way to worm out of finding genuine enjoyment in something by way of a vague objectivity), but it wins you over remarkably quickly, and its idiosyncrasies become its strengths. It exists as proof of process, a film that slowly digs into its own universe, establishing a clear text and a wider world beyond it as the aesthetics slowly evolve over the course of the film's runtime. The textures become richer, the animation becomes smoother, and the finale finds a real footing in its action design. It is absurd and chaotic and it is cinema in its purest form.

The Adjuster (1991)

dir. Atom Egoyan

Are you in or are you out? Enigmatic existence as a game, pieces of lives plucked from the ash and rubble and placed on a board nobody can navigate. The soft folds of the sheets, the abrasive fibers of the carpet, the dusty flats surrounding a house occupying a space as empty as the people who exist within it. Have these people been broken, or does this dig up some uncomfortable fundamental truth that there is a brokenness innate to all of us, falling listlessly through a moonlit sky, searching for some twisted perversion to satiate our hollow souls? More questions than answers, but what else is new; the game continues nonetheless. Egoyan, as ever, unearths a subcutaneous truth about our perilous predilections, shining a light on everyday taboo and the droning mundanity of lurid fetishism as a mechanism to reconcile with trauma. Egoyan weaves a surrealist world and then flattens it all out, oddities and idiosyncracies presented as routine until his twilight cinemascape becomes normalized, luring you into a false sense of security before he twists the knife with an explosive finale.

The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert (1994)

dir. Stephan Elliott

Priscilla certainly has its fair share of rough edges that feel particularly prickly in 2025, between a certain egregiously racist subplot and the shaky casting of a cis man as a trans woman, the modern optics aren't especially ideal. That said, a movie about three drag queens who refuse to compromise their existence for anyone as they travel on an enormous bus through the dusty rural wastes of Australia was a bold swing during the height of the AIDS crisis. Especially a film that navigates the destructive masculinity of its rural setting and builds its central characters out for a knockout final act that includes both heartwarming acceptance and love as well as a truly stunning musical number with enough costume changes to fill the average feature length musical.

Last Embrace (1979)

dir. Jonathan Demme

Incoherent thrillers are the true backbone of cinema, and Demme twists it all into real bizarro non-sequitur surrealism while maintaining a streak of humanity that binds his penchant for character idiosyncracies with the lucid noir darkness of Hitchcock. On its face, each subsequent reveal here feels increasingly nonsensical, the kind of labyrinthine plotting that these kinds of wacky thrillers revel in - but it isn't that any of the pieces here don't fit together - in fact, despite how lurid and strange each sequence is, the dots connect like disparate stars forming a constellation, an image composed from the darkness that somehow makes perfect sense. It's almost as if Demme has composed the film out of a series of elaborate red herrings, where the most consequential images are each intimate moment of humanity amidst a sea of Christopher Walken as a mysterious government spook or Roy Scheider being unceremoniously released from a sanitarium with no context as to why he was there in the first place. Dramatic shootouts in dusty cantinas or among the bells of a Vertigo clock tower are ultimately Demme's way of wielding cinematic cues as a weapon before unleashing a soggy Niagra Falls sequence that turns everything else inside out. Demme's understanding of cinema was always implicit - you can have however much fun you want on the surface while the real film bubbles and boils beneath.

The Road Home (1999)

dir. Zhang Yimou

Features a tangible longing not unlike In The Mood For Love, only Zhang Yimou weaves it at a distance. A story of legacy and distant pasts told largely in flashback, featuring a mesmerizing Zhang Ziyi performance. Simple and peaceful but infused with pure yearning, a love that exists only in furtive glances and tiny gestures, little moments that build into an entire life that we don't get to see - but one we can believe implicitly, leading to a resonant return to the present. What once felt trivial now bears the weight of the world, a necessity to support some kind of cosmic entanglement, two people who were bound by the universe with a gently sewn red cloth.

Rewatches

Unstoppable (2010)

dir. Tony Scott

Some good friends have recently been bingeing Tony Scott's filmography, and it doesn't take a whole lot of discussing Tony Scott before you inevitably feel the need to return to his films yourself. Unstoppable remains a working class, blue collar masterpiece that moves with the same amount of overpowering kinetic force as its central train. An unrelentingly paced thrill ride that reaches the final destination of Scott's filmography, a perfect union of form and function where his slick style thrusts every moment into a heart-pumping adrenaline surge. Almost as bleakly depressing as it is blindingly thrilling, given its stark depiction of clinical corporate avarice that pursues infinite growth over regulations and safety at the expense of the workforce. The executive ghouls sit in offices on the phone, disconnected entirely from the disaster, panicking over the potential stock devaluation to be caused by an entire town being decimated, while the working class blood of America puts itself through the ringer to actually save each others' lives. A window to the past, a mirror of the future.

Monsieur Hulot's Holiday (1953)

dir. Jacques Tati

In search of a moment's peace. The perfect vacation film because Tati so wistfully captures the ephemeral feeling of holiday freedom through the purity of visual and sonic language. Dialogue is incidental, narrative is secondary - though Hulot may be the film's central character, embodying the chaotic nirvana of vacation mishaps, Tati sketches every resident of the seaside down with pristine detail, as if you could turn the camera to anyone else at any given moment and discover a whole new film. Aimless and carefree, the wind carries the film with a light tough, with the effervescent energy of letting the warm air in a summery vacation spot carry you through the day. Even if it all goes wrong, it was still a day watching the sparkling sea, a day listening to fine music in a breezy parlor, a day stuck listening to that swinging restaurant door that you'll remember for years to come. What a lovely holiday.

Comments ()