Japanuary 2025: Reinventing Cinema

When I decided to participate in Ben's first Japanuary challenge in 2021, I didn't join with the expectation of following any kind of structure or engaging with the community. I just stumbled across a post about the challenge and decided it was as good an excuse as any to explore a part of world cinema I wasn't overly familiar with. I certainly didn't expect to meet people who would go on to become some of my closest friends, to start a journey that would lead to me becoming a film critic, or for it to be an enduring mark at the beginning of each year that revitalizes my love for film and brings a community of wonderful people around a shared adoration for cinema's possibilities. And yet here we are at the fifth Japanuary and it feels more exciting than ever - another year of endless possibilities to be shared with my favorite people. Since it certainly feels like Japanuary is the butterfly effect reason that this website exists at all, it seemed fitting to celebrate Japanuary 2025 with a series of pieces highlighting the infinite horizons of Japanese cinema.

So I asked all of my friends; people who inspired me and encouraged me to write more, people who continue to be wonderful writers on film to this day, if they wanted to put together articles about some of the Japanese films they love. I left it completely open-ended - approach it however they see fit, whatever they would be eager to write about. To my delight, I got several enthusiastic responses, and throughout the rest of the month (or what's left of it, I definitely intended to be done with this sooner) we'll be hosting guest features diving into all corners of Japanese cinema.

Of course, I had to ask myself the same question with the same open-ended criteria and find out what would be the most fun to write about. I could comb the depths of V-Cinema's wacky freedom, explore the possibilities offered by the seemingly limitless delights of '80s OVAs, wax poetic about Miyazaki's flawless record, or thoroughly deconstruct one of a thousand different fascinating cinematic movements. Instead, it felt like the possibilities were the point; if the greatest cinema makes you feel like it's inventing form on the fly, reinventing the magical spirit of celluloid, what films embody that reconstructive spirit? Almost agonizing to have to narrow it all down, but out of the endless permutations I've pieced together a collection of brilliant, mercurial cinema that makes these kinds of challenges to seek out and discover new films worthwhile.

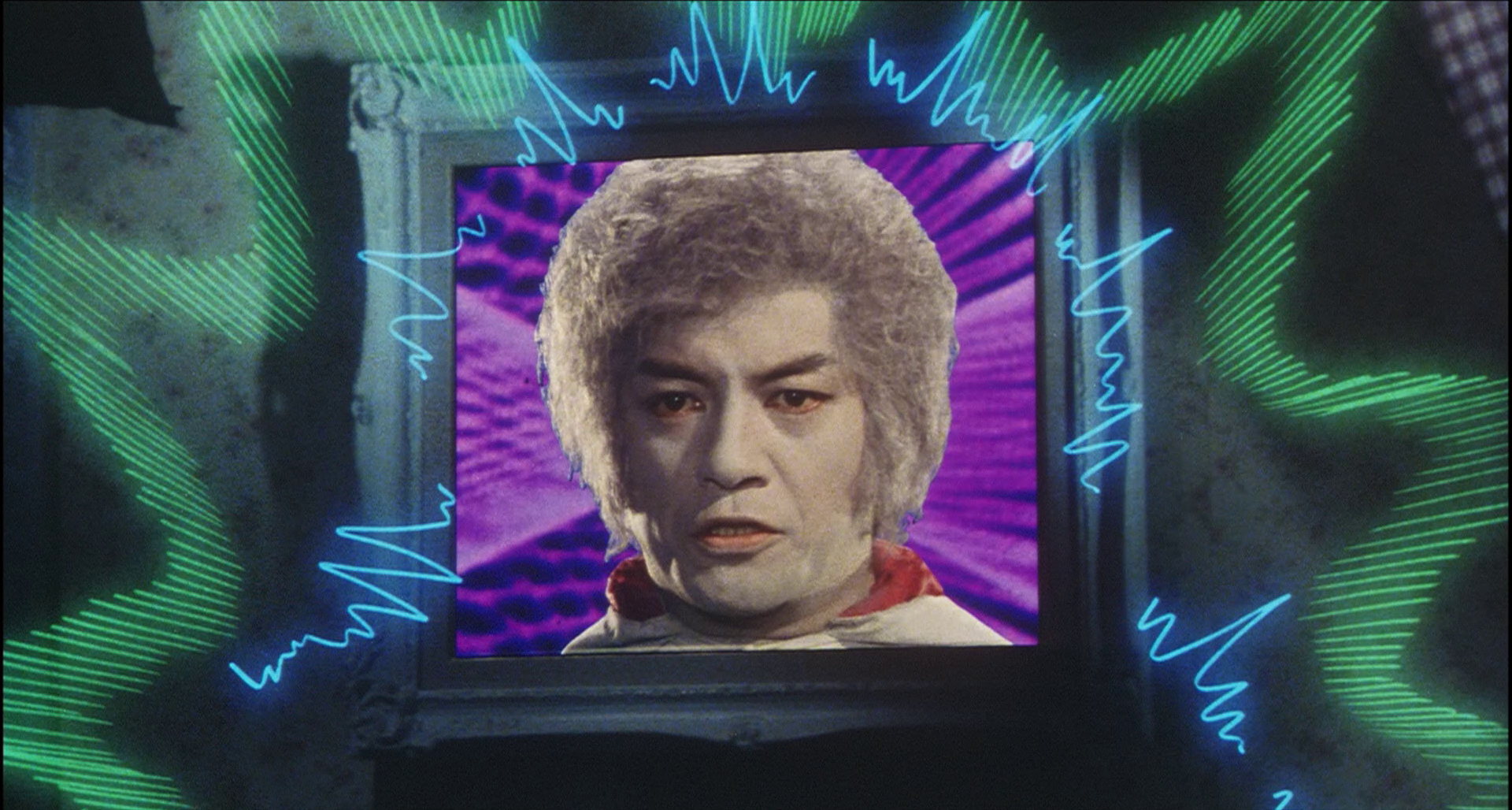

Black Lizard (1968)

dir. Kinji Fukasaku

It's odd to think of Fukasaku's legacy being a roundabout responsibility for the existence of Fortnite thanks to the enduring cultural impact of Battle Royale - maybe in a different timeline his beautifully rendered Star Wars knockoff Message From Space would have generated an entire genre of video games. Before he wrote the blueprint for violent dystopian action, it feels like Fukasaku had already explored a dozen different genres and atmospheres, including the vibrant, mercurial magic of Black Lizard. Its tone and genre explorations as malleable as the gender of its perversely charismatic titular villain, Fukasaku flows effortlessly from hard-boiled detective noir to twisted fantasy and doomed romance. Whether its chameleonic structure comes from its layered sources - a Yukio Mishima play based on an Edogawa Rampo novel - or from the sheer power of drag queen Akihiro Miwa's spellbinding central performance is hard to tell, but it's hard not to be captivated by it all. A colorful, psychedelic splatter of glamorous fascinations, philosophical musings on beauty and impermanence, and the destructive impossibility of love.

School in the Crosshairs (1981)

dir. Nobuhiko Obayashi

Not only would a list about reinventing cinema be glaringly incomplete without the presence of Obayashi, but it could also include just about any of his films. In fact, it was an arduous task to select this one - this could be replaced by poetic musings on the electrifying zaniness of House (though that can be found here), the tender romantic effervescence of His Motorbike, Her Island, or the sonic angst of The Rocking Horsemen. But School in the Crosshairs feels tragically relevant for a film that released over forty years ago, a film that despite its wacky exterior and familiar Obayashi idiosyncrasies, is chiefly about the rising tide of fascism and how it slowly invites and numbs the minds of the susceptible. The school setting makes for a perfect microcosm of a wider reality, wherein the student body is representative of a world where everything is a race for superiority, where staunch individualism creates an air of arrogance that allows for the roots of authoritarianism to seep in. You can either exercise an aggressive iron fist just to feel like you fit in or wield your youthful expression like a hammer, rising to the challenge and standing up for a world that isn't so interested in merely crushing anyone who performs below expectation.

The Man Who Stole the Sun (1979)

dir. Kazuhiko Hasegawa

Kazuhiko Hasegawa's The Man Who Stole the Sun is infinitely mutable and unpredictable, a wild thrill ride that refuses to define itself in any one space or moment, off the rails and careening towards oblivion. Written by Paul Schrader's brother Leonard, it certainly maintains an air of '70s American crime grit, replete with explosive action and corroded psychoses. Yet it still generates an atmosphere of bizarre, post-surrealism levity, teetering on a brink of reality that threatens to dissolve its form into a landscape of dusty radiation and melted colors. A dorky, outsider high school science teacher is driven to the brink of madness by ridicule and isolation and becomes consumed by his fascination with atomic power, constructing a nuclear bomb in his cramped apartment by extracting plutonium from stolen isotopes. Once his project is completed, he takes the city of Tokyo hostage and a genre-bending adventure explodes through the streets, nuclear anxieties filtered through a procedural cat-and-mouse thriller while a bomb-wielding schoolteacher extorts the government into getting The Rolling Stones to play a show in Japan.

The Street Fighter (1974)

dir. Shigehiro Ozawa

The breakout film for international martial arts superstar Sonny Chiba, The Street Fighter stands as a brutal reinvention of action cinema, stripped back and pared down until violence becomes the only form of expression. Depicting a corrupted and decaying world ruled by snapped bones, split flesh, and complete bodily annihilation, the action rules above all else. While Hong Kong's pioneering action cinema was focused on the mesmerizing, almost meditative quality of wispy wuxia or the entrancing nature of motion that electrifying kung-fu allows, here Shigehiro Ozawa transmutes all of these ideas into the evocation of every impact. Focused less on process and more on aftermath, dust coating the lungs and rain splattering against skin as muscle splits and bones shatter, exploding from traditional action into grueling grindhouse perfection. Sleazy, gory, nihilistic, and features a punch so destructive you get to see a skull implode in full x-ray.

Angel Dust (1994)

dir. Gakuryu Ishii

One of the most beguiling and haunting films produced in the era of '90s pop psychology procedurals. While depressing that so many of Ishii's brilliant films are trapped in rights limbo and haven't received proper restorations, there's also something about the persistent standard definition digital fuzz of Angel Dust, befitting its ghostly analogue atmosphere. A decaying Tokyo gives way to a disturbing well of blood and destruction, a creeping web of beckoning self-annihilation that constantly threatens to transform its image into something different entirely. Despite presenting as familiar, Ishii inverts the conceptual simplicity of the procedural and turns it on its head - it's less about the procedure of the hunt and more of the discovery of self, growing slowly aware of how close we all exist to the decay we view as some distant other. With Ishii, the details don't matter - his realities all melt into hazy dreamscapes, painting impressionist images of modern malaise and the subcutaneous allure of violent thrills (and in his later works, these violent thrills are transmuted into emotional catharsis, casting aside the dissonant rage and replacing it with pensive meditation).

A Y.M.O. Film: Propaganda (1984)

dir. Makoto Satō, Saito Shin

I often credit the legendary Ryuichi Sakamoto for igniting a burning passion for the possibilities of cinema within me, it remains a stark memory imprinted in my mind when I first heard the transcendent bells of his theme for Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence. His music was - and is - revolutionary, consistently ethereally beautiful and elevating each film it appears in, contributing not just to the soundscape of Japanese cinema but to cinema around the world. A true musical pioneer who spent decades composing works that rendered pure emotion into a few gentle strokes of ivory, ever experimenting and playing with the limits of what music could become. Fitting of course that before revolutionizing the landscape of film scores he helped pioneer and invent the synth-laden soundscapes of electropop with Yellow Magic Orchestra. Propaganda was created as a send-off for the band before they amicably separated to focus on their solo careers, and it exists as an enveloping synthesis of artists at the height of their ingenuity. A concert film on the surface but serves more as a monumental, avant-garde performance piece where the band portray themselves as imperial fascist overlords who perform dreamy synthpop among a series of surrealist vignettes, an energetic yet oddly tender plea to kill your idols and search for creation within yourself.

Fish Story (2009)

dir. Yoshihiro Nakamura

Sonic resonance through the ages - an endearing ode to the staying power of music and its potential power, regardless of external factors. A joyous punk anthem that injects hope into disconnected narrative structures, stories woven together by the connective tissue of music. Fish Story is an ambitious film for something so deceptively simple, a series of seemingly disjointed narratives only bound by a single song. Under threat of apocalyptic annihilation, each story works its way towards a connection to this song, a structure not dissimilar to Magnolia in its weaving of disparate threads. It spans decades, from the inception of the titular song, written by a group of upstart punks trying to make a name for themselves in the music scene, who view themselves as failures without commercial success. Ultimately the film is a celebration of failure - an inverse of the countless banal platitudes of exceptionalism and greatness that depict artistic success as inherently linked to commercialism. Here authenticity rises above all else, a swan song for fuck-ups and burnouts who find heart in failure, whose honesty in creation births a grungy, nonsensical anthem as a rejection of nihilism, a harmonious song of hope for the many others who find themselves staring at the brink of extinction. Create for the sake of creation, and the failure fades into irrelevance - success is in the act of it all, and maybe someday someone can find solace in that act.

Zëiram (1991)

dir. Keita Amemiya

Creature designer and filmmaker Keita Amemiya wears his influences on his sleeve - his debut film Cyber Ninja melts down a host of visual language from Star Wars to Commando and transports it to a future-feudalist Japan, and his tokusatsu iterations like Kamen Rider ZO and Mechanical Violator Hakaider reconstruct ideas from Terminator, Robocop, Predator, and more. The bizarre world of Zëiram is his most fiendishly original work, a dazzling spectacle of monster action that deserves to be regarded alongside his inspirations. As drenched in hypercolor cityscapes and pastel costume design as it is in hard-edge sci-fi mecha-military technology and goopy, creature feature mania, the film exists in a constant state of rebirth and reinvention. The titular creature shapeshifts through several astonishingly brilliant forms while a cosmic bounty hunter attempts to hunt him down, atmosphere flooded with fog and flame. Transcendent in its oddities and fervently reverent of the magic of monsters, Amemiya's vision is singular and mesmerizing.

Gamera 3: Revenge of Iris (1999)

dir. Shusuke Kaneko

The evolution of the Gamera franchise culminates here, transcending its early beginnings as a cheap Godzilla knockoff featuring a giant fire-breathing turtle. After seven whimsical, goofy rubber monster duels in the '70s and one very terrible film constructed out of recycled old material, the '90s Heisei trilogy revived the once silly turtle kaiju as an aggressive, towering force of nature. Shusuke Kaneko's Revenge of Iris inverts even further, taking his own previously established Guardian of the Universe and turning him into an unsympathetic villain by positioning its protagonist as a victim of Gamera's collateral damage. The seething fury of revenge manifest as a hulking demon, rising from the ashes of something long forgotten and slowly taking form until its massive power becomes its own entity of destruction. Plays off the behemoth implications of something like Hideaki Anno's Evangelion, where the latent emotional instability of youth becomes an unstoppable force beyond control. While the frequent weakness of kaiju cinema is the inherent lack of intrigue typically found among the narratively inert humans dwarfed by battles between gods, Revenge of Iris structures its humanity as essential, core to the battle between these leviathans as they clash in blood and flame. Each action and reaction becomes essential, carefully threading an arc for Gamera's place in the balance of the world. Very easily among the greatest kaiju films of all time.

Kaito Ruby (1988)

dir. Makoto Wada

A full swing romantic comedy in city pop Tokyo, flooded with bubbly colors and fantastical whimsy. Primarily a book and magazine cover illustrator, director Makoto Wada transforms it all into an expressive pop painting, centered by future Golden Globes Best Actor Hiroyuki Sanada as a young hapless salaryman who falls in love with his new neighbor, a self-proclaimed thief and con woman determined to pull off the perfect crime. The resulting film is pure earnest charm, as romance sweeps the pair along through a series of convoluted hijinks, peppered with intermittent musical numbers and screwball sequences. Impressionist pastel cityscapes draped in lush jazz and flickering neon, swimming in twilight romanticism.

Comments ()