Longlegs: Something Underneath

It burrows beneath your skin. A permeating, embedded unease that scrapes and scratches as it worms its way deeper within. Something is wrong, a natural order disrupted, the fabric of the air cut with an inky black presence that exists in an impossible periphery; always there but never perceived. The daylight is suffocated here, a world shrouded in an eternal twilight fog. Patterned violence with no perpetrator. Blood-soaked farmhouses and picket fences. Biblical cryptography and bruised porcelain. Flashes of nightmares brand themselves upon you, crimson seeping ever closer, waiting for the disparate pieces to fall into place, desperately seeking an explanation for such senseless brutality.

Praying won’t save you. You can lie to yourself, blot out the memories, split your mind and live in purgatory; a world of denial and death. It can’t stop the inevitable. You can rationalize, seek empirical truth, something to bind yourself to a reality you once understood. It won’t save anyone. What’s done is done. She’s already dead. Cracked skulls spill whispers, pleas for salvation seeping into the night air, echoes of the extant death a mirror to a forgotten past. Seek justice and find hopelessness. Evil cannot be imprisoned or destroyed.

Longlegs traffics in the unknown, tapping into a tonal atmosphere somewhere between the sheer force of incomprehensible Eldritch horrors and the creeping nerves of occult madness. Oz Perkins lays out the familiar tropes of decades of serial killer thrillers before it and puts all of the pieces into place, only to contort them all into a place of constant unsettling unease. Even these familiar genre comforts aren’t quite right, the rural Oregon twilight casting a haze of anxiety upon everyone residing within this permanent nightmare that threatens all innocence. Borrowing surface level procedural thrills from the likes of Jonathan Demme and David Fincher allows Perkins to revel in the asynchronous oddities, allowing the familiar elements to burn slowly in the background while psyches collapse in the foreground.

The world of Longlegs is one plagued by disruptive presences, not a looming or overpowering threat but a gnawing fog of death, as if something horrifying is lurking around every corner and behind every doorway, exploiting cinematic signals of jumpscares and imminent violence to create a constant anxiety on the edge of your seat while you wait for something to scream out of the darkness. Andres Arochi’s cinematography frames every shot as if there were two people in it, drawing eyes away from the characters with these perfectly placed lines of sight that burst out of the background. You know there’s something there, and by the time you become aware of the shadowy horned illusion’s presence it has already exited the frame, as if it could feel your gaze.

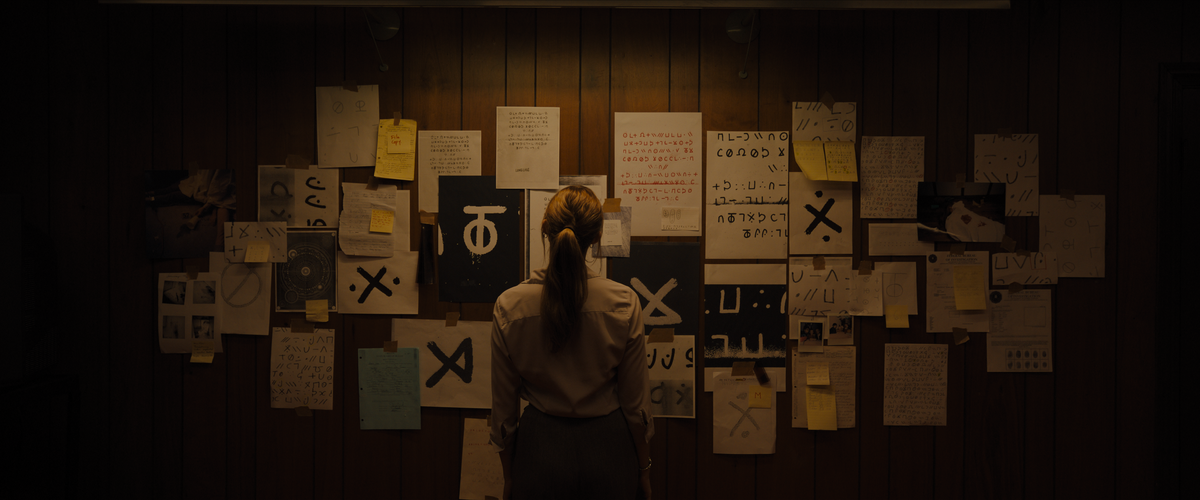

Despite finding its footing by inviting comparisons to Silence of the Lambs or Se7en, Perkins takes an approach closer to Kiyoshi Kurosawa beneath the surface, lacing the film with unknowable dread like Cure or the recent Chime. Like Kurosawa’s films, the mystery never lies in hiding who the perpetrator is from the audience – Nicolas Cage’s implacably terrifying Longlegs appears in the very first scene, caked in snow white makeup with a disquieting smile. The question is never who, but how, trying to parse how his violence could be pieced together and explained. His cryptic, Zodiac-like letters and Satanic iconography elucidate some kind of pattern in the grisly deaths that plague the area but even then these answers remain unsatisfying, the kind of nihilistic hopelessness that every truly horrifying serial killer procedural should coat itself in.

Horror veteran Maika Monroe is the perfect foil for Cage’s unhinged, impossible insanity – her performance as FBI Agent Lee Harker is as disquieting as the gangly terror of Longlegs. She seems permanently uncomfortable in her own skin, as if she doesn’t know who she is or how to exist in her own body, something trapped underneath screaming to escape. The film revels in these parallels and dichotomies, this lurking suffering desperate to escape both characters while one so deterministically strides towards a clean resolution that the other knows cannot exist. Though reports of Longlegs being the most terrifying film of the century may be exaggerated, Perkins is more than capable of getting under your skin, a film with searing atmosphere that assures you’ll be as uncomfortable watching as the characters are uncomfortable existing.

The film’s only stumble in an otherwise brilliantly constructed procedural horror thriller is in its third act construction, as the perfectly paced simmering tension gives way to flat exposition and an abundance of reveals that spoil the horror of the unknown. It’s frustrating to be hit with such unnecessary contrivances in the home stretch when the film has done such an excellent job of telegraphing exactly what it needs to (and really, the film would be better off leaving you with more questions than answers, no matter how ill advised that may be for the majority of theatrical audiences). Thankfully Perkins still knows how to tee up a perfectly nauseating and horrifying final sequence that makes it easy to forget the film’s minor missteps. By the time it reaches the moment that’s been inevitable since the earliest scenes of the film, you just have to look on in abject horror – prayer can’t save you, and you can't save yourself.

Comments ()