Marty Supreme: Manifest Destiny

Josh Safdie's films largely traffic in the wake of the American dream, or about the way that the promise of this country eventually sands us all down into aberrant messes adrift in a sea of post-capitalist chaos. Over time, the focus has shifted and narrowed to be directed at America's grimiest scumbags, the men at the fringes of American exceptionalism, ruthless ideologues who refuse to accept a reality within which they have a capacity to fail, so long as they believe enough in their ability to make it through every obstacle on their way to the top. The extant anxiety of a Safdie film is rooted in the overwhelming sense of desperation; a rancid, pungent atmosphere that bleeds through the screen, the texture of New York City streets providing both an innate sense of promise and a threatening sense of imminent collapse.

Much like Good Time's shaggy, ultraviolet LSD-laced maniac Connie Nikas or Uncut Gems' blood diamond peddling gambling addict Howard Ratner, Marty Supreme's Marty Mauser (Timothée Chalamet) is a shrewd, feverish dreamer who will stop at nothing to achieve what he believes to be his destiny. Marty is far more unassuming than Connie or Howard, at first existing under the familiar auspices of the traditional sports film narrative arc, an upstart with a dream and the determination to make it happen. The first Safdie period piece still takes place in the grimy streets of New York City but has been transposed back to post-war America, a landscape marred by a blend of tactile trauma and galvanizing nationalism. Pitching the protagonist of a thrilling sports drama as the world's next great ping pong player certainly holds an inherent comedic weight to it, but by setting the stage in an era where the sport was still rising to prominence in America and largely existed in dusty pool halls or on the outskirts of a bowling alley, it starts feeling closer to The Color of Money, where the real sport is the hustle of leveraging skill into a quick buck.

Really, the traditional sports narrative arc is exhausted in the film's opening, where a determined Marty hustles part time at his uncle's shoe store just until he can make enough cash to buy a plane ticket to the table tennis world championship. After not getting paid out by his uncle on his last day of work, Marty holds up his coworker for the cash in the store's safe, fully confident in his ability to fly across the Atlantic, win the championship, and return home with more than enough prize money to smooth everything over with his uncle, who desperately wants Marty to take on more responsibility at his store rather than keep pursuing this foolish dream. Of course, anyone familiar enough with the arc of a Safdie film knows well enough that this is only the first bad decision in a neverending spiral that will in all likelihood obliterate the protagonist in due time, but Marty doesn't have a bone of doubt in his body.

Traveling to England with the steadfast determination of every American who has ever believed in their ability to seize their destiny, Marty arrives as the self-proclaimed future of table tennis, the man who will bring about the next step in the evolution of the sport and popularize it across the United States. The tournament's provided housing isn't acceptable for someone of his perceived stature, so he puts himself up at the Ritz, starts flirting with visiting actress and socialite Kay Stone (Gwenyth Paltrow), and tries to get in the good graces of her wealthy business magnate husband Milton Rockwell (Kevin O'Leary). Despite his seemingly bottomless well of arrogance and taste for brutally dark humor that seems to offend everyone in his vicinity, a combination of the pure power of cinema and Chalamet's commanding screen presence make a strong case that Marty's belief is still rooted in a reality where he wins it all and becomes America's favorite son.

Such is the power of American exceptionalism, of the facade of manifest destiny. The gravitational pull of determination and drive creates an unwavering air of faith in ability, that through sheer willpower nothing could stop us from achieving our predestined claim on this earth. When Marty loses in the finals to rising Japanese table tennis star Koto Endo (Koto Kawaguchi), it doesn't even cross his mind that he could lose purely on the basis of ability. The match was unfair, Endo was cheating, the Japanese players shouldn't have been there at all because of the post-war travel ban. While most sports dramas would center a monumental loss like this as the fulcrum for a sweat-laden training montage or as the climax to punctuate a hero's journey into gracefully accepting loss, Safdie merely uses it as the establishment for a spiral into utter chaos that frequently puts the maddening tension of Uncut Gems to shame.

Returning home without the prize money or glory he anticipated having to send himself into the stratosphere of household table tennis names across America, his prior actions immediately begin to gnaw at his heels, and suddenly the film is mired in the sweaty, desperate anxiety of Howard Ratner betting on an absurd parlay or Connie Nikas drowning a security guard in LSD-laced Sprite. Marty's journey to self-actualization quickly becomes an odyssey of collateral damage, his pure faith adrenaline-ride built on the back of his own self-made mythology colliding with everyone in his surrounding and slowly destroying them. The persistent strength of Safdie's films is the roaring cacophony of their ensemble casts, and Marty Supreme is no different, an endless collection of brilliantly placed character actors who breathe life into the destructive and chaotic spiral of Marty Mauser as he searches for absolution.

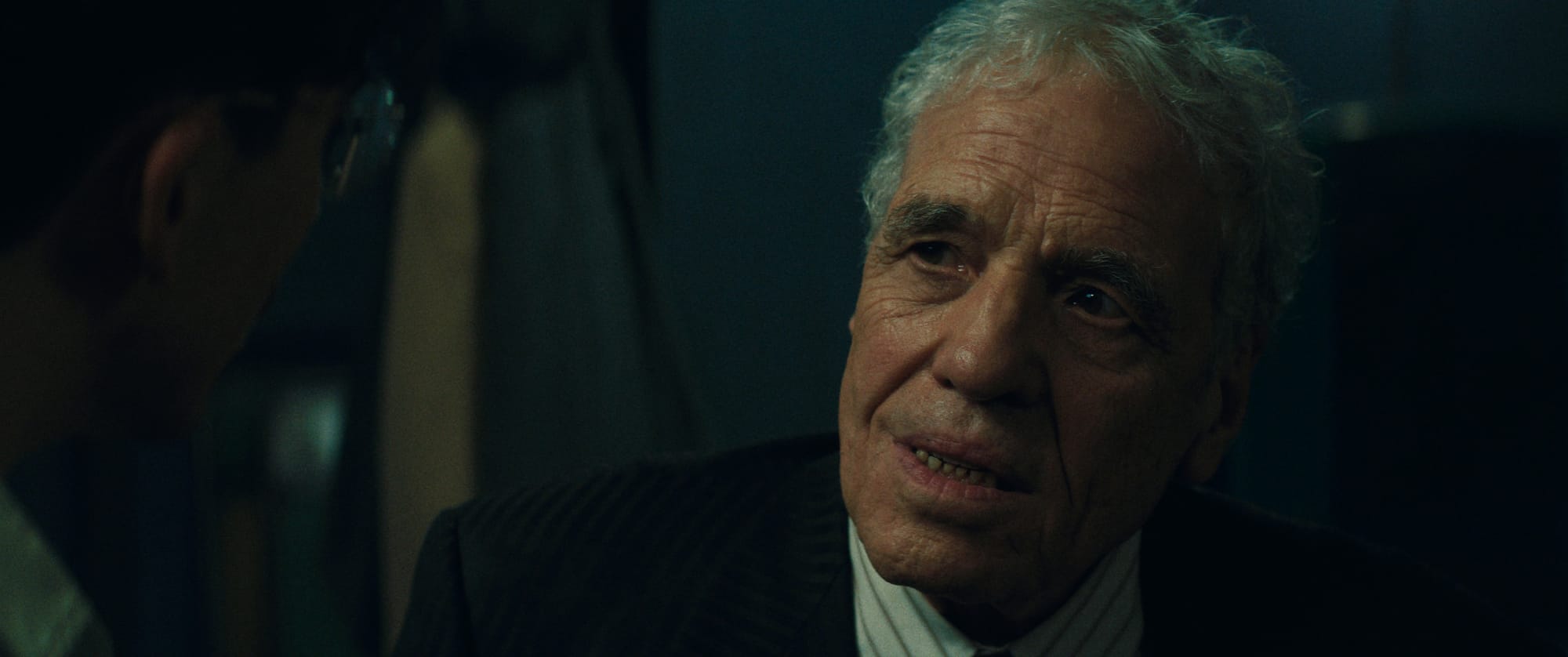

Everyone Marty encounters, no matter how rich, poor, powerful, or insignificant, is a means to an end, a potential way out of his slowly building debt to everyone in his life. His longtime friend Rachel (Odessa A'zion) might be carrying his child as a result of her affair with him, but she's only a useful tool to Marty as an escape route or as leverage to rip off mysterious gangster Ezra (Abel Ferrara, completely embodying the filth and grime of his own cinema as a powder keg of violent energy). His cabbie friend Wally (Tyler, the Creator, who maintains the perfect level of Safdie energy enough with his own personal brand that he settles in seamlessly with his surroundings) is only as much of a friend as he can help fill Marty's pockets by way of conning ping pong casuals out of their hard-earned cash. The elegant class of Kay Stone might be an attractive notion to Marty, but he's more attracted to what she represents, a woman he might just be able to fleece for a meal ticket by exploiting her desire to feel like a star again. Her husband sits at the top of this fragile tower of wealth and exploitation that Marty so desperately wants to weasel his way into, but the pen industry titan is the only one who can meet Marty at his level.

Kevin O'Leary playing Milton Rockwell is such brilliant meta-casting that it's almost a shock that someone like him would accept the role at all – though the fact that he did creates its own self-parody layer of meta-commentary on the kind of completely disconnected person you become at that level of wealth. While he parades around angrily in real life complaining about New York's newest mayor not making concerted efforts to give billionaires special treatment, his counterpart in the film is a petulant child whose self-interest starts and ends at humiliating others in an effort to enrich himself. There is no such thing as negotiating with him because he knows the needy will come crawling back at their most desperate hour, willing to accept any terms necessary to get what they need. It's never more true than it is for Marty, whose nightmarish whirlwind of aggressive individualism has led him on a roller coaster of highs and lows almost more volatile than that of Howard Ratner's litany of won and lost bets, flooded with blood and sweat and tears as he slowly alienates or destroys everyone around him.

It's exceptionally exhilarating filmmaking, not just thanks to the hypnotic directorial fervor of Josh Safdie but to the entire team he's constructed. Ronald Bronstein's whip smart script keeps the verbal cacophony and dialectic madness of previous Safdie films while never compromising on coherence, Darius Khondji's cinematography manages to blend the dazzling glamour and feverish gravitational pull of Uncut Gems with the grimy grit of Se7en, and Daniel Lopatin's droning, pulsating synth score puts the elation of Uncut Gems to shame, particularly next to the brilliantly anachronistic selection of '80s new wave bangers that underline the film's most impactful moments of kinetic levitation.

By the time the film winds down from its climax, a sequence of thrilling intensity that reaches the blood-pumping adrenaline rush of Challengers' final tennis match, the dust settles on a very different world surrounding Marty Mauser, who more than any other Safdie character is actually granted space to reflect on the seemingly endless deluge of reckless individualism that does little more than destroy us all and leave us hopelessly empty. Eventually we come to realize that we might just be more than ourselves, and that the sum of our experiences are not counted in wins or losses. It doesn't mean we aren't all born with a little bit of destiny in our hearts, hoping to be the next one on top.

Comments ()