My Favorite Film Discoveries of 2024

Movies are always good. And they always have been.

Movies are always good. And they always have been. Now that we've concluded a season of highlighting and awarding the best of this year, it's time to reflect on the year in new discoveries and what's stood out among a sea of new watches. Really, any random handful of the 130+ films I've marked as standout discoveries for this year would be just as meaningful as what's presented here; it's hard to skip over including films like Fruit Chan's Made in Hong Kong, Muscha's Decoder, or Joe Dante's Gremlins 2: The New Batch, but Noboru Taemoto's Gokaiger Goseiger Super Sentai 199 Hero Great Battle is probably too powerful to be contained in a few brief words. So, in the interest of marketable brevity, I've compiled a clean list of ten films that were some of my favorite discoveries in 2024.

My full Letterboxd list of my favorite movies I discovered in 2024 can be found here.

Nocturama (2016)

dir. Bertrand Bonello

The characters in Bertrand Bonello's mercurial Nocturama are not revolutionaries. They have no defined ideology, no grasp on anything beyond the elastic timeline that shifts from procedural deconstruction to paranoid psychosis. Some of them spout juvenile political jargon that masquerades as manifesto but it lacks all substance, others are disaffected accessories, others lack conviction entirely. Some don't seem to understand their purpose at all. Bonello's film is not a radical political doctrine, much less a reactionary one; it is instead, as defined in its haunting final moments, a cry for help. Sympathetic to a generation of disparate, lost youth who are only able to find camaraderie in acts of violence, corroded by stiff individualism and abandoned by the state. This violence is self sustaining, youth who have no outlet for expression and see no hope for a meaningful future on the horizon channeling their frustration in the only way left that makes sense, and the state responding in earnest with bloodshed that perpetuates this void of suffering.

Monsters Club (2011)

dir. Toshiaki Toyoda

Lyrical martyrdom, or at least the façade of it. Frozen isolationism as anarchic revolution. I have been abandoned, and so shall I abandon all else. Disillusionment decomposing beneath a pristine white blanket of snow. Muted, peaceful, numb. A solitary purgatory. A realm between the infinite emptiness and the blood-soaked gears of avarice. All that's left is violence deeply rooted in visceral trauma, immeasurable grief, and an unforgiving cycle of monotony. Nothing changes. Soul hardened by anger. The world is lost. Maybe even hopeless, doomed to spin through the vast empty cosmos and slowly erode. That doesn't mean we can't live. We have to.

His Motorbike, Her Island (1986)

dir. Nobuhiko Obayashi

On love and memory. On listlessly drifting through the infinite present. On heartache and desire, delicately dancing above threat of despairing boredom. On hazy city pop dreamscapes and the colorful lilt of yearning. Romance as effervescent expression, a warm feeling escaping into the fuzzy twilight glow. Love purified and distilled into monochrome melancholy and resplendent joy until it becomes interchangeably mirrored. As much pain as there is comfort. To flirt with death and experience life. Tangibly one, moving through space in unity, always. The world is a lot more colorful when you're next to me.

The Boy Friend (1971)

dir. Ken Russell

The master of cinematic excess applying his endless talents to a freewheeling and extravagant musical, a dizzying display of chaos that rivals the towering psychosis of The Devils. Only here instead of religious bloodshed and forbidden lust as the driving force for madness he replaces it all with acid-drenched post-modernism, an endlessly wild explosion of delirious artistry. The thematic drive of The Boy Friend reverberates through Russell's own dreams, a firm belief that if you really mean what you say in the rigorous process of creation, you can't go wrong. It rarely does for Russell, especially when you can seemingly so effortlessly craft a film of numerous and completely distinct jaw-dropping setpieces complete with gorgeous choreography. Pure cinema.

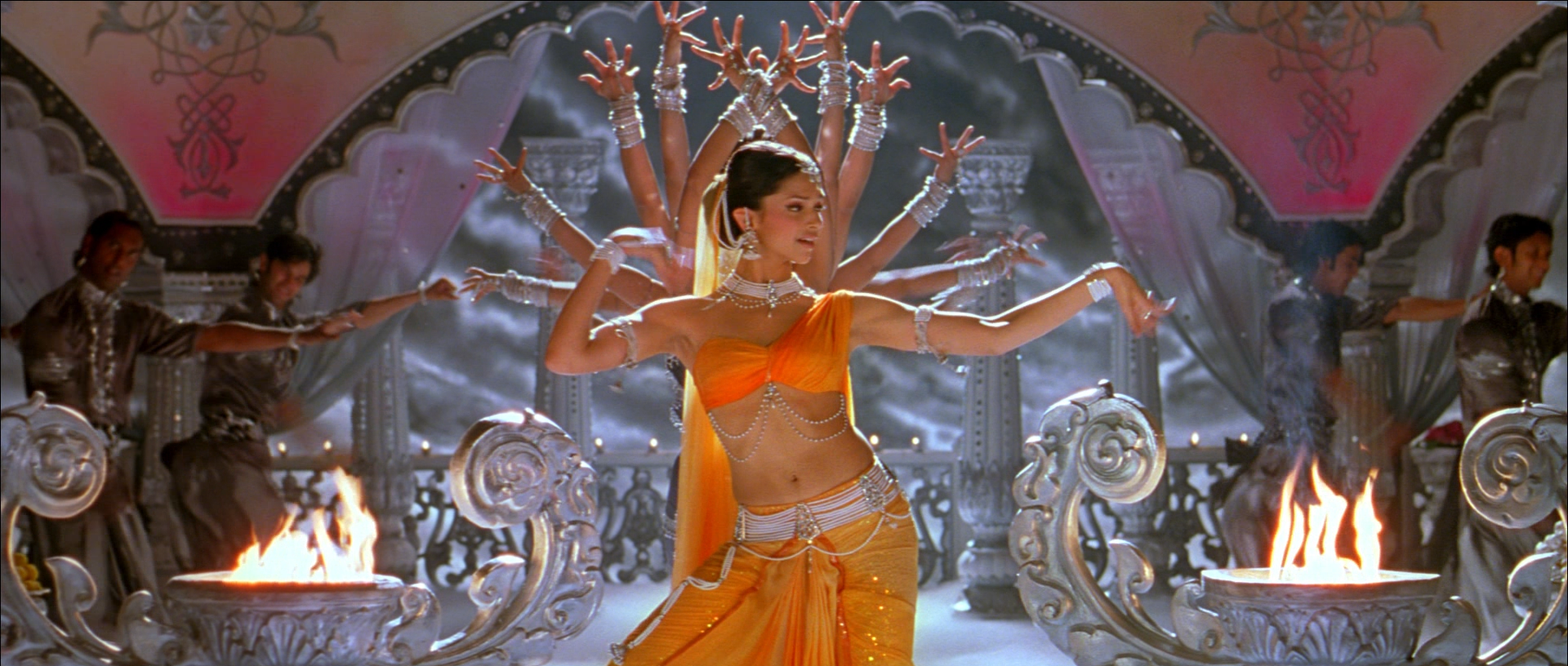

Om Shanti Om (2007)

dir. Farah Khan

Certainly manages to rival Ken Russell himself in terms of sheer blistering musical excess, but Farah Khan's vision of spectacle is filtered through a history of national cinema, dedicating itself to the purity and magic inherent to filmmaking. Khan has no interest in simplicity - a sprawling fantasy that's constantly reinventing itself, shifting between tone and genre at ease and resulting in a stunning extended finale that earns its sweeping final moment. So adeptly weaves its multi-layered narrative; transcending lifetimes, rebirths of identity, and the everlasting persistence of romance, that it completely escapes the constraints of its complexities. A soaring love of the power of cinema threaded into three stunning hours.

Rachel Getting Married (2008)

dir. Jonathan Demme

When you've watched Jonathan Demme's Stop Making Sense 20 times trying to glean an understanding of its infinite well of humanist collectivism, eventually the only way to dig deeper is to search through the rest of Demme's filmography to gain a more holistic sense of the way he approaches filmmaking. From TV movie Who Am I This Time? to his tender, sweeping approach to a Spalding Gray monologue Swimming to Cambodia, or even his directorial debut Caged Heat - a sleazy, Corman produced women in prison exploitation film - Demme's dedicated, earnest thoughtfulness shines through, always finding an angle of kindness or anti-authoritarian subversion. It never shines brighter than in Rachel Getting Married, a staggering and soaring portrait of love, struggle, healing, and pain, deep wounds and an earnest well of humanity. Perhaps Demme's greatest achievement in his understated blending of tone and genre, shot with a digital neorealist affect as it quietly shifts through a cavalcade of emotional upheaval. Rests so heavily on Anne Hathaway's lead performance and she never stumbles, perfectly toeing the line between her extant pain and the joy she desperately wants to find. Demme was truly one of the greats.

A Matter of Life and Death (1946)

dir. Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger

Doubling as one of my favorite discoveries as well as one of my most memorable cinema experiences of the year, I find it hard not to be enraptured by a film about the enduring love found in the romantic destiny between an American and a Brit. It's even more effective when you're able to see Powell & Pressburger's dazzling, fantastical masterpiece on the big screen, introduced by the legendary Thelma Schoonmaker as she waxes poetic about Michael Powell's enduring romanticism and the legacy he left that reverberates through Scorsese's filmography. When love is everything, there's no question of the sacrifices we would make, not a moment of thinking before stepping onto that staircase. To die for love is everything, but to live for love is to experience the tangible spectrum of color and wonder, underscored by the spectacular Techicolor reality on display next to the cold, stagnant sterility of heaven, trapped above, only peering down at the world below.

Out of Sight (1998)

dir. Steven Soderbergh

The sweeping romance of Powell & Pressburger is one thing, but the intangible romantic tension of Soderbergh is another entirely - tapping into unspoken desire through lush cinematography and sheer confident charm. Some of the most powerful and natural chemistry ever unleashed on film, complicated by a spiraling series of prison escapes, crime capers, and cat-and-mouse thrills. Soderbergh revels in the texture of it all; typically atypical editing, radiant red and blue lighting, and a dazzling score of soft piano and smooth bass. Certainly feels like the center of what anyone might mean when they say "they don't make them like this anymore," but that would only be true if Soderbergh had ever stopped being a monumentally energizing creative force in filmmaking, and despite his best attempts to retire, he has two new films releasing in 2025.

Robot Carnival (1987)

dir. Hidetoshi Ōmori, Hiroyuki Kitakubo, Hiroyuki Kitazume, Katsuhiro Otomo, Koji Morimoto, Mao Lamdo, Takashi Nakamura, Yasuomi Umetsu

The anime anthology is a staple of Japanese filmmaking, but it's also often a mixed bag of results - for as many unassailable greats like Memories or Neo-Tokyo there are countless anthologies that are disparate and empty, or only contain a couple shreds of brilliance among a series of mediocre or drab shorts. For as fascinating and experimental as it is, even The Animatrix has a few weak points. Robot Carnival stands tall above the rest, in all likelihood the single greatest anime anthology ever produced. It helps that Joe Hisaishi immaculately scores every short, tying them all together under a magical soundscape, but the thematic thread of robotics in all different forms makes for a beguiling and beautiful holistic experience outside of the individual shorts.

What's Up, Doc? (1972)

dir. Peter Bogdanavich

It's the year of Hundreds of Beavers and madcap screwball chaos is in - and it's possible nobody ever did it better than Peter Bogdanavich, Barbra Streisand, and Ryan O'Neal. Doesn't just lift from the visual idealism of Looney Tunes but directly invokes it, as charming as it is endlessly hilarious in its constant stream of gags and setpieces. Pure chaos born out of an endless onslaught of misunderstandings, misplaced confidence, and awkward interactions, culminating in a stunning car chase that could only come from the chaotic excess of Friedkin's '70s.

Comments ()