The 25 Best Films of 2024

25 films from 2024 that represent the breadth of what cinema can be; genre across the spectrum, from microbudget to blockbuster, representing cinema from across the world.

Movies are always good. There's an ever-increasing sentiment that cinema is in decline, that the theatrical experience is dying because there's nothing worth seeing, that all Hollywood has to offer is blockbuster slop with bloated budgets and inert narratives. The reality is that a year doesn't go by without dozens of outstanding films, and that no matter what you prefer to watch or how you prefer to watch it, there will be something out there that's worth your time. We need not submit ourselves to the notion that we should be actively disengaging from the films we watch, that the only way to enjoy things is to accept whatever is in front of us as simplistic popcorn entertainment. We can be challenged, engaged, captured, dazzled, and excited by films all at once. The magic of cinema never dies if you choose to seek it out and connect to it.

Amidst strikes, pandemics, and the rise of sleazy tech bros desperate to invent something capable of stripping all humanity from art to cover for their own lack of ingenuity, cinema remains an enduring force. A force of humanity and perseverance; it only takes a few people playing video games in a basement or wandering the streets of a New England suburb to make something with as much creative fervor as a crew of hundreds launching stunt people into the sky in the outback wastes of New South Wales at 100 miles per hour.

It's easy to limit yourself to a clean ten for a list like this - it may even be the smarter approach, to present something succinct and digestible for the prospective reader, but ten feels both limiting and counter to my own thesis that there will always be countless films to discover. Here I present 25 films from 2024 that represent the breadth of what cinema can be; genre across the spectrum, from microbudget to blockbuster, representing cinema from across the world.

For as many films make it onto this list, there are just as many well deserving of recognition that didn't make it; films like Junta Yamaguchi's dazzling time-loop romantic comedy River, Yugo Sakamoto's blisteringly paced action comedy Baby Assassins 2, Steven Kostanki's zany puppet horror Frankie Freako, David Hinton and Martin Scorsese's soulful ode to Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger Made in England, or Mati Diop's transcendent documentary Dahomey. For the very best, read on; these are my favorite films of 2024.

25: The Order (Justin Kurzel)

Justin Kurzel's hauntingly prescient thriller is drenched in fog and flame, a grungy and hard-edged adrenaline surge that owns its pulpy period atmosphere. A decidedly bleak film not just in its crime procedural genre trappings but in the chillingly familiar image it paints, depicting the rise of white supremacist organization The Order in the 1980s across the Pacific Northwest; the facade of virtuous family values atop violent, seething hatred in search of blood to spill. Almost more chilling is the blunt hollowness of it all, a finely tuned hopelessness in realizing that the people who are supposed to prevent this kind of violence are wholly inept, a crack in the image of peace these institutions represent. Lush vistas of rolling mountains and verdant forests accompanied by Jed Kurzel's haunting atmospheric score infuse every silence with a palpable dread - while Jude Law's FBI agent plays into a rote procedural masculine fantasy, Nicholas Hoult's Bob Mathews sows the seeds for a revolution that's becoming realized 40 years later.

24: Soundtrack to a Coup d’État (Johan Grimonprez)

Though unlikely to be recognized as such, Johan Grimonprez's revolutionary jazz documentary is the most wildly successful feat of editing this year. A visual essay comprised entirely of meticulously composed archival footage that manages to weave a fascinating narrative tapestry, chronicling the Cold War history of Congolese independence through the lens of jazz as a radical force. Editor Rik Chaubet's filmic composition reflects its subject, a freeform and mercurial presentation that effortlessly floats through its many threads in support of sonorous brass freedoms. As electrifying an experience to watch as it is infuriating to see the way colonial powers continue to exert control. The kind of thing cinema was made for.

23: Wallace & Gromit: Vengeance Most Fowl (Merlin Crossingham, Nick Park)

Certainly and frequently hilariously Wallace & Gromit's Mission: Impossible movie, but also a far more effectively pitched image of the ways artificial intelligence threatens to rob from us the joys of creativity and expression. There are few things more delightful this year than seeing Aardman's meticulous and expressive claymation in full swing; like a cozy cup of tea with an old friend.

Seattle Film Critics Society Nominee for Best Animated Feature.

22: A Different Man (Aaron Schimberg)

Equal parts biting body horror, deliriously acrid comedy, cosmically destructive romance, and perfectly pitched reflexive satire; Aaron Schimberg's shapeshifting film of identity and ego is a whip smart whirlwind of unraveling threads. At any moment feels like it could go in a thousand different directions and it still manages to find itself consistently subversive without ever missing a beat or becoming overbearing, not just thanks to its finely tuned script but carried into the stratosphere by its powerful trio of leads. Less interested in finding a neat or moral conclusion than it is in consistently complicating the psychological dynamics between its characters in a way that better reflects the deep well of human flaws that exist at some universal core. The lingering note is as disparate and haunting as it is decisively hilarious and oddly surreal.

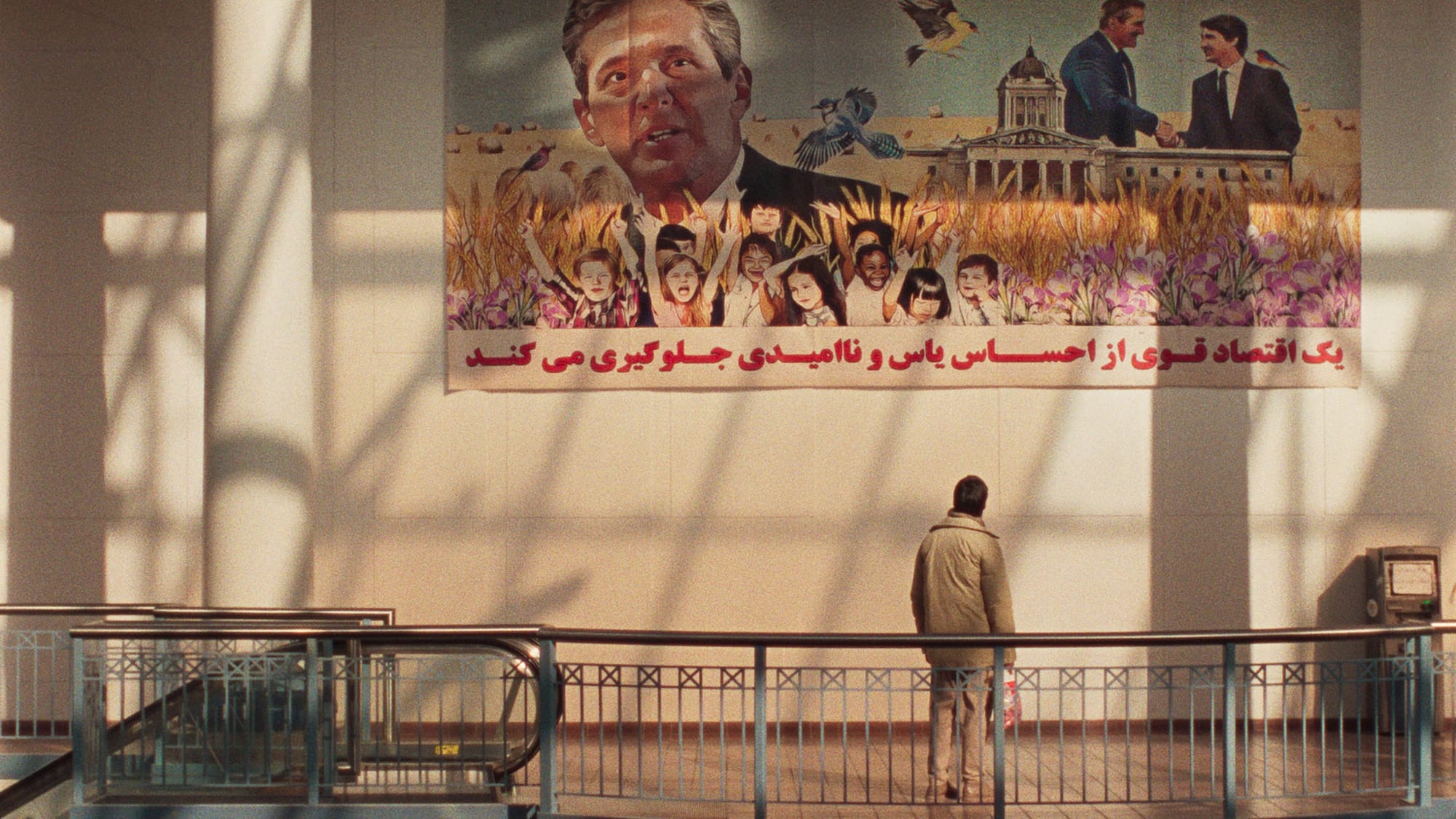

21: Universal Language (Matthew Rankin)

As we enter a world where a younger generation of filmmakers pull from a whole new set of influences, it's nice to see a western director pull so confidently and directly from the warm humanity of the Iranian New Wave. Matthew Rankin's Universal Language is a confident collision of Kiarostami and Makhmalbaf's reality warping, warm docufiction imagery alongside dry Canadian humor and the stark brutalist architecture of Winnipeg. Conjures as much of the innocent wonder of Where Is The Friend's House? as it does the dismal, dry nihilism of I Hired A Contract Killer, and Rankin never seems to miss a beat in making his film as wholly unique and novel as it is strangely familiar. Fitting for a film he describes as an autobiographical hallucination, following a self-insert character played by Rankin himself who travels home to Winnipeg after leaving his job in the Quebec government. Mysteriously blending culture and image, his alternate reality version of Winnipeg has been infused with Tehran, a collision that allows him to play with the tropes of Iranian cinema while interrogating his own childhood and his reconciliation with familial bonds.

20: Nickel Boys (RaMell Ross)

RaMell Ross has done one of the most electrifying and fascinating things this year by crafting a film that adopts a first person perspective without ever feeling cheap or gimmicky. Nickel Boys, carried heavily and tenderly by Jomo Fray's ingenious cinematography, is gentle and flooded with heartfelt interiority by way of its perspective, each image lingering on its extant humanity as eyes fall on interlocked fingers, beaming reflections, and the simple minutia that we carry with us as treasured memories. Despite being one of the year's most destructive and devastating films in its wider context, implications, and its oppressive abusive reform school setting, Ross manages to keep it from ever feeling exploitative or reliant on trauma; focusing on the moments of levity and love as Elwood and Turner navigate a treacherous existence in a world that desperately wants them to fail.

Seattle Film Critics Society Winner for Best Cinematography

19: Love Lies Bleeding (Rose Glass)

One of the year's most visceral and tactile films, Rose Glass gives every bead of sweat weight and propulsion as erotic tension escalates by way of blunt force raw physicality, adrenaline-rush thrills, and electrifying body horror. Feels as energetically raw as Shinya Tsukamoto's anxiety-flooded explorations of humanity and iron and as grotesquely contorting as David Cronenberg's visions of the decaying human body as we seek our deepest unrealized desires. Though despite finding common ground with Tokyo Fist and Crash, Glass is a stoic and bold original, making every moment feel as violently fresh as it is inevitable, a seemingly foregone conclusion that rapidly whips through pulsing synths and aching muscles. Equal parts thrilling, sexy, and disgusting, as all cinema should be.

Further Love Lies Bleeding discussion in episode 53 of I'm Thinking of Spoiling Things.

18: Rebel Ridge (Jeremy Saulnier)

After the bloody, comic novelty of Murder Party and the ensuing dizzying brilliance of Blue Ruin's cold vengeance and Green Room's explosive punk chaos, it's been a desolate near decade since visionary director Jeremy Saulnier hit it out of the park. 2018's Hold the Dark was a shaky and hollow outing that was abjectly miserable without hitting the mark on anything remotely revelatory, and Rebel Ridge was held in filmic limbo for years after suffering from pandemic shutdowns and actors deserting the project. Thankfully, despite being locked in an undeserving Netflix prison, Rebel Ridge is a phenomenal outing that reminds us why Saulnier is one of the most fascinating filmmakers working today, spinning a First Blood-like narrative into an examination of deescalation as a rejection of corruption and state sanctioned violence and racism. The film's depiction of systemic corruption and legalized theft illuminate an America where no matter how virtuous your intentions, a system designed to enrich the oppressors will always win.

Further Rebel Ridge discussion in episode 56 of I'm Thinking of Spoiling Things.

17: La Chimera (Alice Rohrwacher)

Cinema through a viewfinder, a collision of past and future caught in a foggy haze. Alice Rohrwacher's beautiful magical realist vision of a dusty, working class '80s Italy is as transportive as it is dreamy, a hazy recollection of memory in search of lost love. Combining warm 35mm and grainy 16mm photography it all becomes implacable and almost phantasmagoric despite its presentation, drifting between realities and unearthing a history long forgotten while Machiavellian forces conspire to flatten all of time into an empty husk of capital.

Full review on The Twin Geeks.

16: Red Rooms (Pascal Plante)

A genuinely dark examination of the way the internet and our collective, infinite interconnectedness has sanded down our empathy and turned us into fetishistic voyeurs in constant search of thrills. Pascal Plante's construction makes for something almost icy and placid despite the constantly escalating tension and stakes, creating a dread-laced atmosphere that centers digital destruction filtered through a lens pieced together from a myriad of influences. Reflects and refracts ideas and tactile, scuzzy, true crime decay by way of Fincher, Assayas, Haneke, or even the chilling peacefulness of Kiyoshi Kurosawa while remaining consistently mercurial and evasive. Grants almost no insight into protagonist Kelly-Anne while also slowly revealing that she may be little more than an empty husk, hollowed out and desensitized by the crimson glow of her monitor. Enthralling and haunting in every way.

Seattle Film Critics Society Nominee for Best International Film.

15: Hit Man (Richard Linklater)

The ultimate Linklater film - earnest romanticism trapped between notions of performative identity, ego, self-actualization, and the systemic issues inherent to the American justice system. Somewhere between the charming and goofy local interest story of Bernie and the passionate yearning of Before Sunset is a film where certified movie star Glen Powell plays a dozen different absurd characters without missing a beat, all while coming to terms with his own identity by way of sheer romantic chemistry. Every movie should be a romcom constantly threatening to become a noir where a police procedural collides with an erotic thriller and characters debate the ethics of state sanctioned murder. Only Linklater is brave enough to do it and capable enough to make it a delight to watch.

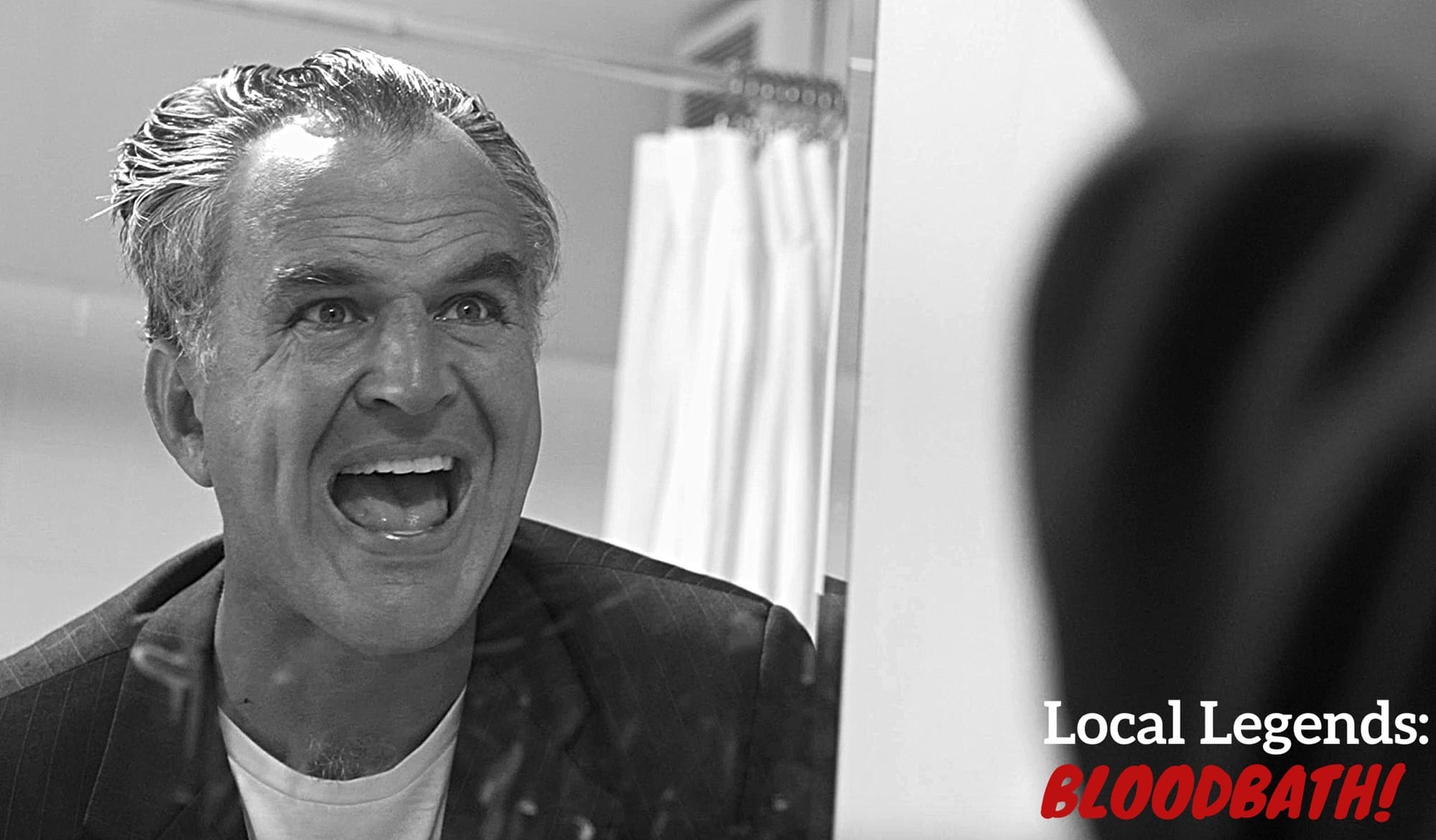

14: Local Legends: Bloodbath (Matt Farley)

Matt Farley's Local Legends is an independent cult masterpiece, a beautiful and earnest ode to creation for the pure joy of creation. A reflexive, autobiographical effort that constantly seeks to question itself and its own existence while caught in the frustrating and unavoidable cycle of needing to turn a profit. Over a decade later, a lot has changed for Matt Farley - now an enigmatic internet phenomenon with a dozen more movies and a catalogue of music large enough to sustain himself on. So when does joy turn to obligation, and when does the creative process become stifled by a now urgent need to forge constant output to continue providing for yourself and your family? It would be impossible for Farley to answer that in any straightforward manner; thus Local Legends: Bloodbath is born, a comically vicious deconstruction of ego where Farley turns his own "Nicest Man In Showbiz" persona into a violent outburst set on eliminating every speck of negativity from his life. Though Bloodbath is certainly one massive home run setup and punchline, there still lies at its core a warm sentiment from a guy desperate to shed all the pretense and to go back to making things just for the sake of it, without the persistent anxiety of the process generated by being a part of the zeitgeist.

13: Rap World (Conner O'Malley, Danny Scharar)

We've reached a space in the cultural milieu where there's a collective desire to put on the rose-tinted glasses and fantasize about the digital fuzz of the 2000s - and we've certainly gotten our fair share of cheaply etched nostalgia bait. It's a mixed bag, but much of it is washed and sanitized, trying to erase the uglier sides of that period to avoid any sense of being brash or offensive. Conner O'Malley's Rap World might just be the first piece of aughts period filmmaking that instead revels in a bunch of total dirtbag shitheads, painfully accurately aimlessly wandering a desolate suburbia as they drift between basements and various hangout spots getting high and playing video games while chattering endlessly about the dope rap project they're going to work on any minute. O'Malley's bizarre alien energy might capture a vibe so specific that it's as worthy of contempt as it is raucous laughter, but he continues to emanate an energy like he's the only one on the right wavelength. Maybe one beyond all of our perception.

12: Twilight of the Warriors: Walled In (Soi Cheang)

Action as both unstoppable force and immovable object, a frenzied collision of claustrophobic dynamism expressing a relentless hunger for freedom. Trapped in a labyrinth of tangled wires and rusted metal ruled by chaos, justice served with cracked bones and spilled blood. Its spaces oppressive and suffocating as it yearns for the open sky, overcranking a mutating blend of action hysteria as its gritty realism gives way to a floaty wuxia fantasy. Violent expression as a kaleidoscopic reflection of past, present, and future; in search of a way forward through loving dedication to the soul of a country and its history of action. Hong Kong's action cinema has always felt limitless - and Twilight of the Warriors is as singular as the films it reveres, a full throttle odyssey where the only rule is to dedicate everything to the art of action.

Seattle Film Critics Society Nominee for Best Action Choreography.

11: The Brutalist (Brady Corbet)

Monumental in its construction, taking on the form of its subject as a massive and cold monolith with a well of secrets lying beneath the facade. The sheer weight of its ambition sands down its rougher edges and more bluntly unnecessary choices, a great American epic that follows in the footsteps of the finest cinema on the rotten fabric of capitalism our landscape is so impossibly reliant on. Packed wall to wall with immaculate performances, stunning photography, and features one of the year's finest scores. Unsurprisingly elucidates the deep and unshakeable contempt that most of this country's ruling class hold for any and all immigrants, a reality that creeps quietly through the film through its decades long timeline and lingers with the knowing, gut-wrenching notion that this timeline has never wavered, and we are as rotten as we ever were.

Seattle Film Critics Society Nominee for Best Picture, Best Director, Best Cinematography, Best Editing, Best Screenplay, Best Original Score, Best Lead Actor (Adrien Brody) and Best Supporting Actor (Guy Pearce). Winner for Best Production Design.

10: Hundreds of Beavers (Mike Cheslik)

Slapstick cult comedy Hundreds of Beavers is the year's greatest surprise, a delirious microbudget independent romp that spent two years marinating in exhaustive post production. A lightning fast, gag-a-frame rollercoaster that seemingly effortlessly pulls an endless series of miracles to achieve the funniest and most creatively endearing film in years. As true to form as any imagined version of a live-action Looney Tunes cartoon could be, shot in scratched, fuzzy black and white with the slightest undercrank that gives it all a cartoonish zip as a man trapped in the frigid tundra faces off against the titular hundreds of beavers (also known as four grown men in Chinese beaver mascot costumes).

9: No Other Land (Basel Adra, Hamdan Ballal, Yuval Abraham, Rachel Szor)

Essential cinema. A harrowing document of hope beneath the ruin of oppression in occupied Palestine, an urgent portrait of humanity as a people fight to exist in their homeland. As devastating in its stark documentation of lived atrocities as it is powerful in its depiction of unshakeable perseverance. Finds the common ground of genuine humanity in an unimaginably inhumane existence as Palestinian Basel Adra forges a bond steeped in revolutionary action with Israeli Anti-Zionist Yuval Abraham. Critically, its lingering note cuts to black in October 2023, ending at the start of the Israel-Hamas war and the siege of Gaza; this suffering, this destruction, this pain - is not new. It has been destroying a people for decades while the west watches idly by, complicit in the apartheid atrocities.

Seattle Film Critics Society Winner for Best Documentary Film.

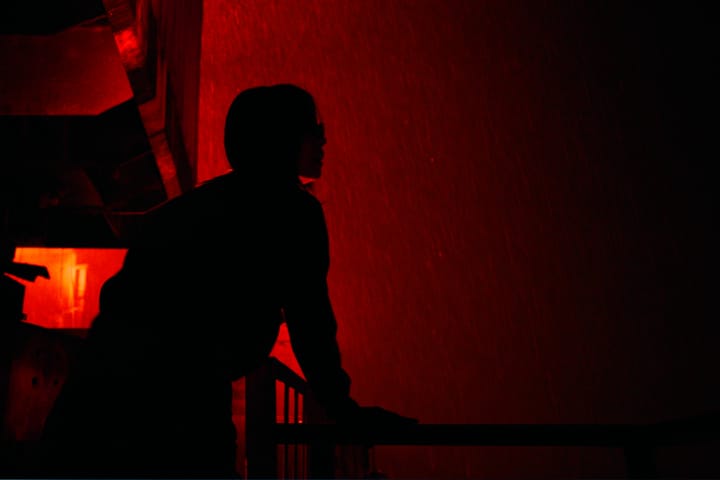

8: Chime (Kiyoshi Kurosawa)

Kurosawa’s potent cinematic language comes from his ability to cultivate contemporary anxieties through isolated lenses, from the disillusioned cityscapes of Cure to the crackling digital haze of Pulse or the suffocating latent societal pressures of Creepy. The imagery is striking but familiar, haunting frames always depicting a corroding isolation of spirit. His environments shift to match their subjects but it is ever evocative of something itching at the back of your mind. Cure beckons towards an inner animosity, Pulse buzzes through the wires of a corrupted digital existence, Creepy burrows deeply beneath the illusory reality we commit ourselves to. Here, Kôichi Furuya’s crisp cinematography draws an almost precision engineered existence, so sanitized and clean that it is devoid of personality; distant, eroded. A world that has become so painfully monochromatic that the only color left is the crimson extracted through thoughtless rage.

7: Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga (George Miller)

George Miller isn’t foolish enough to imagine he could live up to – let alone top – the dizzying heights of Fury Road’s thrill ride, but he also knows that wouldn’t be any fun anyway. Instead, Furiosa reconstructs the mythology of the wasteland so effortlessly that it’s strange this piece of the puzzle has been missing for nearly a decade, feeling less like a reverse engineered prequel and more like a lost beginning that was always there but never seen. Where most prequels are plagued by a stifling determinism, Furiosa doesn’t look to explain Fury Road so much as it seeks to enrich it, and Miller producing a whole new $170 million epic with the express purpose of taking his previous masterpiece to an even higher level of intensity is, simply put, one of the most baller things a director has ever done.

Seattle Film Critics Society Nominee for Best Picture, Best Cinematography, Best Production Design, Best Costume Design, Best Visual Effects, Best Supporting Actor (Chris Hemsworth). Winner for Best Editing, Best Action Choreography, and Villain of the Year (Dementus.)

Full Review on The Twin Geeks.

6: Sing Sing (Greg Kwedar)

Art as freedom. Art as expression and reconciliation, as kindness and humanity amid systemic oppression and a lifetime of being put into boxes. Empathetically directed material is elevated to tender expression by way of its litany of authentic performances from former Sing Sing inmates, something that quickly becomes a reverberating catharsis of men finding true soul in themselves and in each other. A simple, almost conventional narrative arc envelops the film but its importance fades into the background as each liminal moment of process becomes the lens to understand the characters, anchored by Colman Domingo's sensational performances as Divine G.

Seattle Film Critics Society Nominee for Best Picture and Best Ensemble Cast. Winner for Best Lead Actor (Colman Domingo) and Best Supporting Actor (Clarence Maclin).

5: All We Imagine As Light (Payal Kapadia)

Payal Kapadia's mesmerizing, understated portrait of Mumbai contains the year's most tender and beautiful romance, a dramatic and impossible love played to the buzzing glow of warm texts and the hushed whispers of secret meetups, an authentic adoration caught between religion and culture. Bifurcated narrative protagonist Anu yearns for authenticity while her parents bombard her with arranged marriage proposals, desperate for something real among centuries of tradition demanding otherwise. Her coworker Prabha caught in another stage of the same patriarchal incarceration, a husband she barely knows halfway across the world, attempting to pay penance for years of estrangement with anonymous gifts. Underneath it all Kapadia weaves a beautiful tapestry of working class Mumbai, social unrest and the desire for freedom from the crushing oppression of classism and corporate greed. Magical neorealism, a glittering cityscape full of humanity, hope, and love that shines through every barrier.

4: Challengers (Luca Guadagnino)

Luca Guadagnino wielding Justin Kuritzke’s acid-soaked script makes for a spellbinding piece of cinematic delirium, a slow build of a thousand infinitesimal character motions that has your heart beating like you’ve been darting around a court all day before it even reaches its most exhilarating moment. There is no rise and fall here, it is all anticipation, waiting for the rollercoaster to drop as it races to the peak at full speed only to fly completely off the track. The film’s triumphant finale is an explosion of cinematic ecstasy, with cinematographer Sayombhu Mukdeeprom (a frequent collaborator of both Guadagnino and Thai slow cinema pioneer Apichatpong Weerasethakul, a stylistic synthesis which feels impossible and yet is fully present here) oversaturating each moment with stunning stylistic flourishes. Dizzying tennis-ball POV shots and hazy, sweaty step-printing, a double split-diopter and shots pointing towards the sky from beneath the court, as what was once a seemingly irrelevant local tennis match has become the greatest cinematic adrenaline rush in years. Guadagnino lays it bare and leaves no time for questions – existence is lust, existence is desire, and all we can do is play the game for the thrill of the adrenaline, in search of an ineffable cosmic singularity.

Seattle Film Critics Society Nominee for Best Supporting Actor (Josh O'Connor). Winner for Best Original Score.

Full review on The Twin Geeks.

3: Evil Does Not Exist (Ryūsuke Hamaguchi)

Ryūsuke Hamaguchi's Drive My Car may go down as one of the best movies of this decade, and equally serene and contemplative Evil Does Not Exist isn't far behind it. It comes from the earth itself, an organic film born out of the emotional strength of composer Eiko Ishibashi's soaring score, a gentle stream of harmony that brings every falling snowflake and rustling blade of grass to life. Only fitting that a film so steeped in its environment would be so becoming of it, a desparate plea to find peace with the ground beneath us, seeking truth through a reckoning with the way nature flows through us. Hamaguchi looks for where instinct begins and ends, what reactive response is born into us and the innate presence of destruction that is forged into us by external forces. Evil does not exist because it has become our nature; just another day at the office. Instinct.

Seattle Film Critics Society Nominee for Best Original Score. Winner for Best International Film.

2: Anora (Sean Baker)

Sean Baker's cinéma vérité approach to filmmaking always points to the same thing; that there's no need to be so individually direct about any one specific issue when there's a poisonous rot so deep rooted in our culture that everything above it is fundamentally broken. Finding the shadow beneath the performative veneer of a transactional existence. The glossy surface of Anora's Cinderella romance is a thin facade that covers a devastating portrait of the way capital poisons everything it touches; everything has become completely indistinguishable and it's no longer even clear what we're doing, why we're doing it, or what the end goal is. Just a mindless submission to chasing a hazy ideal. By the time the film reaches its crushingly silent conclusion it becomes clear this was the only way it could end, so tangled in performing so many layers of self that it's impossible to know what's real anymore. The lack of interiority is a feature, not a bug - the kind of extant hustle that forces the working class to forget themselves applies to the corrupted souls of the oligarchy in the inverse, so caught up in the idealism of wealth without any authenticity underneath. Ivan is in love with a fantasy until it no longer serves him, and Ani is in love with a fantasy believable enough to feel authentic until the falsity has become stretched too thin. Much closer to the heightened anxiety of the Safdies than the humming neorealist approach Baker typically takes, but almost reveals itself to be a kind of F For Fake style feature length deception, where Baker's expression of larceny is to wave a madcap screwball comedy at you only to hit you harder than ever with his own reality shattering gut punch when the snow starts to fall. A brilliant dance of genre and expectations; it may not be anything exceptionally new for Baker, but it is another reminder that he's one of our finest filmmakers.

Seattle Film Critics Society Nominee for Best Picture and Best Editing. Winner for Best Screenplay, Best Ensemble Cast, Best Director and Best Lead Actress (Mikey Madison).

1: The Beast (Bertrand Bonello)

Contemporary and eternal fear, what happens as we slowly succumb to frigid isolationism and digital loneliness, the crippling existential anxiety of an inscrutable impending tragedy applied to the entirety of humanity and stretched over the course of two centuries. Bertrand Bonello consumes the simple conceit of Henry James' novella and extrapolates it across the decline of the human condition, a world of people too fearful of pain to accept its presence, in turn erasing everything born from emotion and love. Bonello's time-bending triptych weaves genre and visual language into a mosaic of fascinations, crafting an immaculately composed elegant period romance only to slowly undercut its sweet simplicity with a terrifyingly tangible home-invasion paranoia thriller complete with corroded digital artifacting. By casing it all in a bleak, sterile dystopic future devoid of emotion and ruled by a now concerningly palpable blanket of artificial intelligence Bonello finds empathy in our persistent yearning for connection. Léa Seydoux's pained eyes glean an endless desperation for more, trapped in an infinite number of worlds where different forms of fear take root and cause suffering. We desire each other, pain and all. There must be beautiful things in this chaos.

Comments ()