The Anarchic Realisation of Self in Tetsuo: The Iron Man

The mechanisation of work is presented as an extreme metaphor of the mechanisation of self, lost in a seductive moray of the industrial. Each machine is taken into the self, every new implement morphing your physical identity.

Though an original work of surrealism in its own right that exists to just be that, Tetsuo: The Iron Man is a film animated by the paranoias, anxieties and insecurities of the time. It is a film of colliding ideas and narrative direction, at points an almost clear film about revenge for a hit and run; always a narrative about being defined by the environment around us and also, among so many things, an extreme exploration of personhood.

The most immediate and obvious anxiety the film unpicks is around modernisation and a new age of industrialisation. A rapid growth in technology, and the ever increasing mechanisation of the late 80s, is evidently on display. There’s the perennial fear, as new technology is adopted or created to carry out — or innovate upon (or even expedite) — existing processes, that many will be made obsolete. As Japan pushes further and further into being a nation of mega cities and a leading voice in technology, this becomes part of cultural identity. Machines take on the roles of man and thus it makes sense that the traditional salaryman at the centre of this film would yearn for the machine. The mechanisation of work is presented as an extreme metaphor of the mechanisation of self, lost in a seductive moray of the industrial. Each machine is taken into the self, every new implement morphing your physical identity.

The salaryman is already such an overt symbol of Japanese life, of a specific kind normality. To skew him into a mechanised monstrosity, but one that welcomes this grotesque metamorphosis, is obvious but powerful social commentary. His escalating foe, the character who willingly mechanises himself, becomes a necessary symbolic pair in order for the film to present this capitalist struggle of growth, competition and industrialisation that starts to overwhelm all around it. Japan is seen as a nation of tradition and serenity, this sits at odds with the mega city way of life. This film takes images linked to tradition and then skews them towards the corrosively mechanical.

The heart, then, is a cynical film about loss of self and corroded identity. The push to a life of technology overrides the soul and makes us monsters. One need only look at the production design which is so immaculately focused on making the mechanical something that is grotesque in a carnivalesque way. The sound design is where this message really lies, though. So much of the upsetting and abrasive elements are merely sonic, as surprisingly prosaic images (eating off of a fork, for example) are paired with grating metal sounds. Discomfort is from the incongruity, an assault on the normal by the mechanical. The film is focused around a traditional, normative unit being destabilised: male salaryman and his female partner have their life upended by an interaction with a new type of man, one who has engaged in self mechanisation. Their joining is forged in destruction, and in a mechanical collision, and from that point their reality is indelibly shifted.

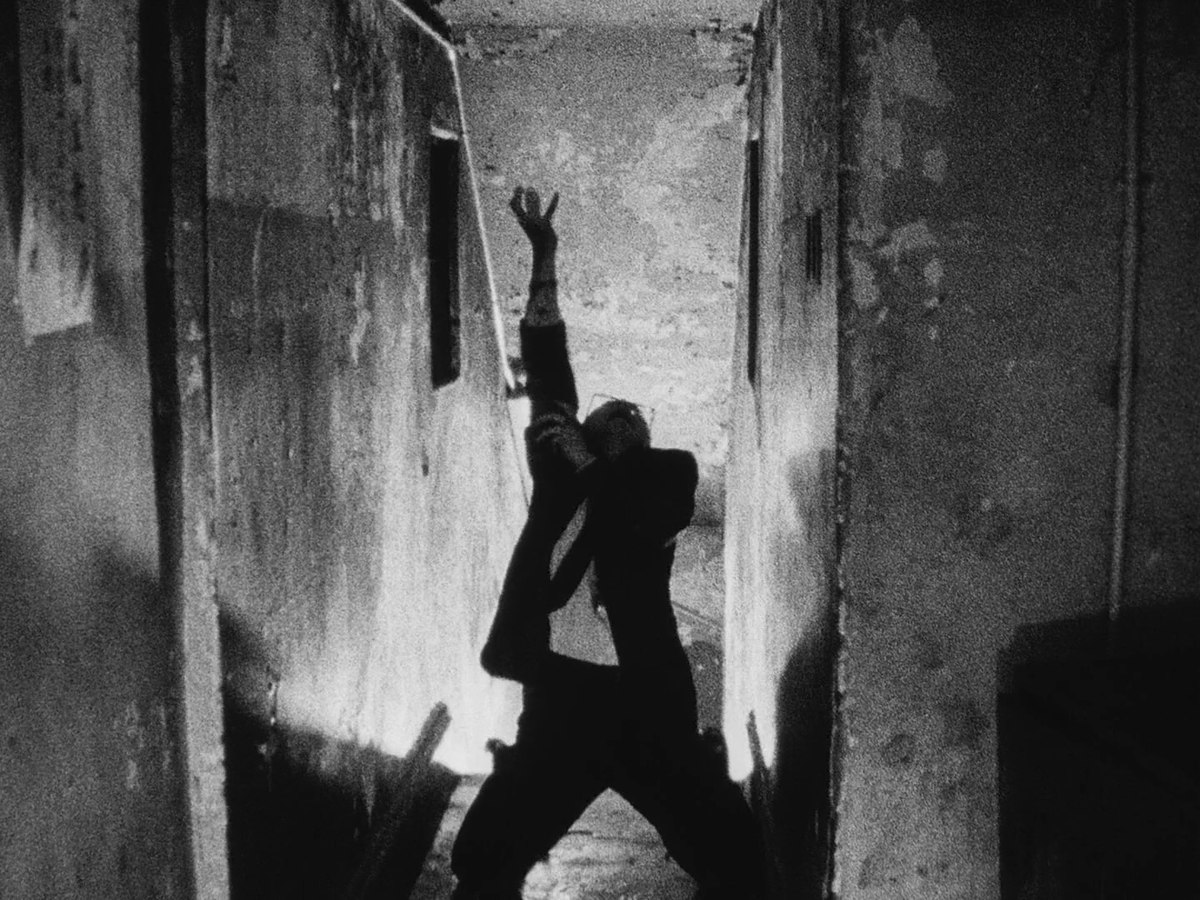

It’s not a cynical film, though. Tetsuo: The Iron Man is not bleak and sour, nor is it bitter and sincere. It is an openly ridiculous film of dark, and at points slapstick, humour. The filmic style is avant garde in a punk rock fashion. It’s an exuberant explosion of post-Japanese New Wave style, adding extra layers of anarchic experimentation and expressionistic abstraction to a pre-existing transgressive template. There’s also an arc towards victory and freedom, as the film becomes a film of liberated identity. There certainly is a visual concern about the aesthetic change in Japan, of a push towards a corrosive industrialism that is a threat. However, this sits alongside an actual narrative about self realisation. It’s a film that is very easy to apply queer reading to, as the arc takes us through a chrysalis into a grand rebirth.

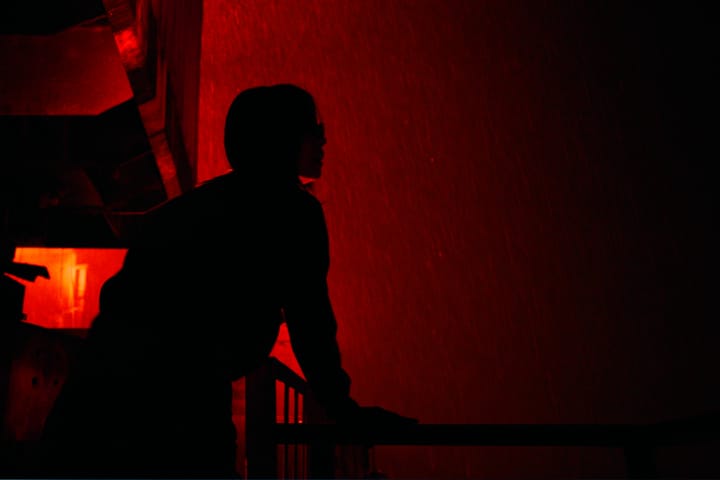

Before fully embracing this, there’s another insecurity at play: that of disease. The corrosive metal that takes over these persons disfigures them and dehumanises them. This is first gained through experimentation on the self — a drug analogue could easily be applied — but this social disease is passed on through interaction and then corrodes all. The sexual imagery that pervades the film certainly supports this reading, as does the overt homosexual overtones that dominate the film. One could very regressively read the film as an AIDS panic picture, or similar. This isn’t fully supported, though, as the film is more about the paranoia around these things than these things themselves. Hallucinatory moments have our salaryman frequently threatened by the coded feminine. Women appear as monstrous, as aggressive or as belittling — they are a threat to him. This doesn’t feel like misogyny, more a way of presenting a deep rooted insecurity that traditionalist society has always conveyed as toxic.

This read fits the arc is the film so well. Two men are separated by insecurity until they create a gestalt of liberation. It is seen as socially damaging but it ends up as proud, blatant and liberating with the amalgamated character professing the power of love. To go back to the industrial reading, it is about embracing the new and finding power in it. One must move with the times or be swept away. The sexual reading is more potent, though, and in keeping with a counter cultural aesthetic. The very image of tradition is subverted and this subversion is made to seem monstrous up until the point those involved can find their liberation. Thus, it is about the pejorativised made to see themselves as inhuman due to difference.

Comments ()