The Phoenician Scheme: Immaculate Chaos

Every line would be the funniest thing you’ve ever heard if not for every other line.

With The Phoenician Scheme, Wes Anderson captures chaos with paradoxical precision. It’s a marvelous achievement where the film manages to be freewheeling, anarchic and delightfully messy, all while staying immaculately controlled. Though the primary strength is in its comedy, this aforementioned dichotomy is where resonance lays: order is mapped onto disorder to reckon with a corrupt world, and to mirror a quest for control amongst chaos.

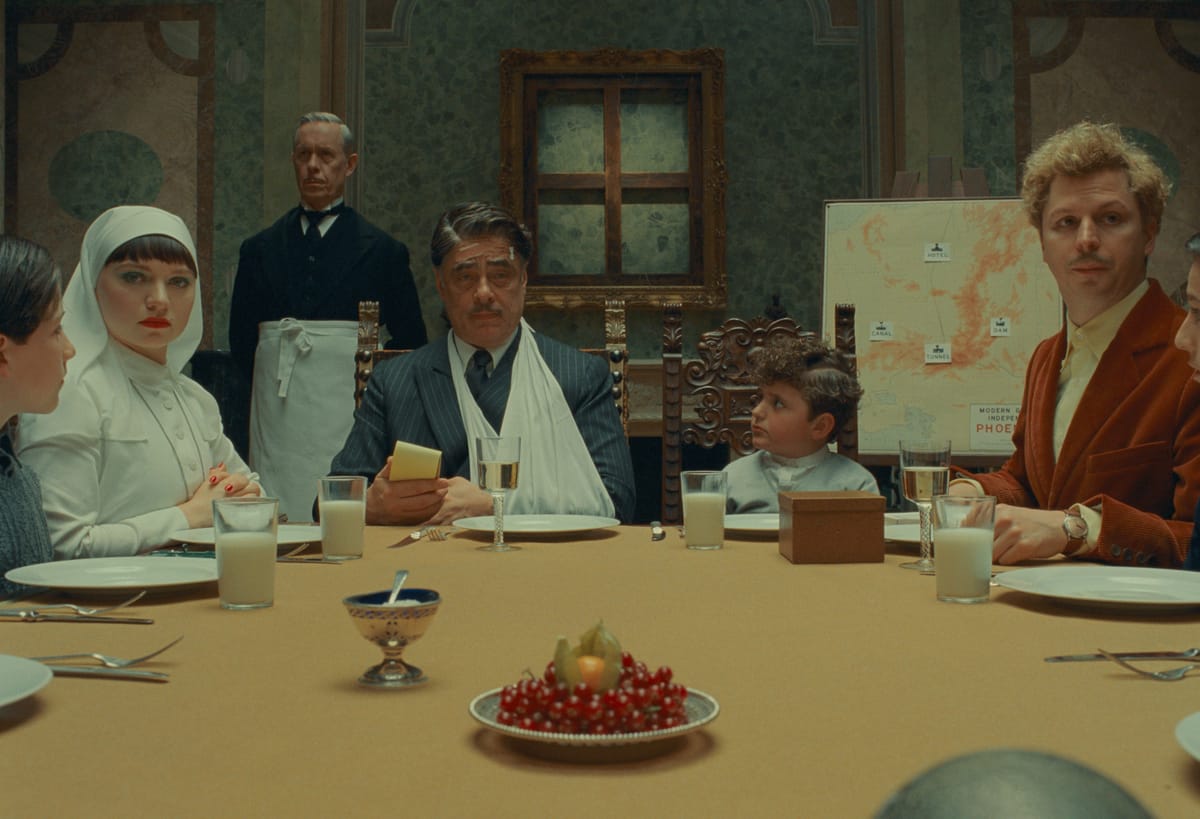

The narrative is unwieldy yet precisely segmented. The immaculate mise en scene of the Anderson picture finds a framing device: our lead character lays out their plans, each step belonging to a separate box and we then unpack the narrative in a deftly literal fashion. Our lead is Zsa-zsa Korda, played by Benicio Del Toro. A legendary swindler, this exploitative business man is a grand fraudster, an evil entrepreneur wanted by every state — always attempting a far reaching grift to get his. He’s a cartoon villain but the film positions him as our hero, a terrific perspective to hang the film on. There’s an amorality to him that produces the film’s chaos, his existence is a collection of running jokes that the film gets so much mileage out of — the main one being how he is constantly the victim of assassination attempts. He’s a marvellous comic creation built out of bon mots. His reckless attitude and constant subterfuge make him the perfect ever shifting centre.

Here is the brilliance: the anarchic core. The plot is all about pulling off a wild scheme but the real narrative is an emotional arc for Korda. Mia Threapleton plays one of his many children, but his only daughter, Liesl, and the only child he recognises. She’s in training to be a nun and thus we have our odd couple dynamic. The pristine nun is a pair for the Anderson aesthetic: formal restraint, the immaculate. The course of the film is wonderfully chiastic, as Korda (through proximity to death and family) mellows while Liesl becomes more rebellious. The shift in Korda’s character is traditional, yet very satisfying. It’s not as rote as you might fear, also, as a wonderful middle ground is found by using these foils. The film celebrates madness and finds beauty in it. A positive kind of anarchy is born out of amorality. Anderson’s most political work in that it shows the normalised, far reaching corruption and then preaches living radically and actively to combat this.

Really, though, it’s just a triumph because of how creative it is. It is an utterly joyful ripping yarn filled with incredible jokes. Every line would be the funniest thing you’ve ever heard if not for every other line. It’s not just Anderson doing Anderson again, there’s the sight gags you’d expect brought about through precise control, but our characters are atypical and the humour primarily comes from them. It’s a brashness that takes us back to The Royal Tenenbaums and The Life Aquatic. It is whimsical but it’s an acerbic whimsy and the comedic style feels very unique to the film, as it constantly forges and reforges its own in-jokes. You can feel yourself missing gags as you parse other ones, every phrase precision tooled to be madly funny. Everything in the production is so controlled and this smartly indicates that you should let the chaos happen. Confusion and obfuscation are wielded so that the true focus is character. The plot is contrived as a kind of aesthetic statement, a device to add to the humour and to fit alongside the overall production. One may balk at the Anderson perfectionism but, here, the film so benefits from it.

Every performance is incredible. A murderers row of known and new talent that thrill no matter the screen time. Michael Cera is the standout and gives one of the greatest comedic performances you’ll see. It is funny because it encapsulates what the film is doing, through layers of obfuscation and self-aware fun. Playful, academic, austere and carefree. A paradoxical joy that reaches transcendent heights through being hysterically funny and so aesthetically ambitious. It just goes for it, Anderson more stretching a style to new spaces rather than relying merely on old tricks. We’ve reached the stage of the Wes Anderson film as genre, and this is a highlight therein.

Comments ()